As previously reported,1 the Policing and Crime Act 2017 (the Act) introduced a series of major changes to the U.K. financial sanctions regime. The changes, which came into force on April 1, 2017, included the creation of new civil powers for HM Treasury’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) to impose monetary penalties on companies and individuals for breaching financial sanctions. On April 3, pursuant to its obligation under the Act, OFSI released new guidance on its approach for imposing monetary penalties (the Guidance). The Guidance helps clarify OFSI’s intended case-assessment and penalty-quantification processes. The Guidance also confirms that OFSI intends to exercise its new powers in line with the approach to enforcement that has been adopted by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in the United States. While there are clear similarities between the Guidance and OFAC’s Economic Sanctions Enforcement Guidelines, companies that engage in activities that are subject to U.S. and U.K. financial sanctions should also understand the important differences between the two penalty regimes.

UK Nexus

The Guidance helps clarify OFSI’s jurisdictional reach in responding to breaches of financial sanctions. A sanctions violation does not have to occur within U.K. borders to make it subject to OFSI’s authority, but there has to be a connection to the U.K. A U.K. nexus might be created by, for example, a U.K. company working overseas, transactions using clearing services in the U.K., actions by a local subsidiary of a U.K. company (depending on the governance), actions taking place overseas but directed from within the U.K., or financial products or insurance bought on U.K. markets but held or used overseas. These examples are not exhaustive or definitive and whether or not there is a U.K. nexus will depend on the facts of the case. While the U.K. nexus is not a new concept, the Guidance highlights that OFSI’s jurisdictional reach — like OFAC’s — is broad.

If OFSI becomes aware of sanctions violations in another jurisdiction, it may use its information-sharing powers to pass details to relevant authorities, if appropriate and possible under English law.

Decision to Impose a Penalty

The Guidance states that OFSI can respond to a case before it in a number of ways, depending on the given factual circumstances. These responses resemble the responses available to OFAC for an apparent sanctions violation, and include:

- imposing a monetary penalty;

- referring the case to law enforcement agencies for criminal investigation and potential prosecution;

- issuing correspondence requiring details of how a party proposes to improve their compliance practices (even where OFSI concludes that the person did not know and had no reasonable cause to suspect they were in breach);

- referring regulated professionals or bodies to their relevant professional body regulator in order to improve their compliance with financial sanctions; and

- closing the case where no violation is found or where it determines that no further action is reasonable and appropriate.

OFSI does not explain these responses in more detail, and the use of the word “includes” suggests that the list of responses in the Guidance is non-exhaustive.

In deciding on the appropriate response, OFSI considers a variety of factors (“case factors”), which largely parallel the “general factors” OFAC uses to determine whether to impose a penalty or make adjustments to the base amount of a penalty under its Enforcement Guidelines. These case factors include:

- voluntary, materially complete disclosure in good faith;

- whether the funds or economic resources were directly provided to a designated person;

- whether there was circumvention;

- value of the breach;

- harm or risk of harm to the sanction regime’s objectives;

- knowledge of sanctions and compliance systems;

- behaviour (e.g., whether the violation was deliberate);

- professional facilitation (“facilitation” is considered a form of sanctions circumvention, and individuals who act on behalf of or provide advice to others as part of their job may be considered professional facilitators);

- failure to apply for a license for a licensable transaction, or breach of license terms;

- repeated, persistent or extended breaches;

- reporting of breaches to OFSI;

- failing to provide information when required to do so;

- public interest; and

- other relevant factors.

These case factors play an important role throughout the enforcement process. In addition to being relevant in determining the general type of response to a case before OFSI, the case factors also play a crucial role in determining the amount of any civil penalty imposed by OFSI, because they help assess the seriousness of any breach (as described below).

Minimum Threshold for a Monetary Penalty

Before OFSI can impose a civil monetary penalty, however, a minimum penalty threshold must be met. First, by the terms of the Act, OFSI may only demand a monetary penalty if, on the balance of probabilities, there has been a breach of, or a failure to comply with an obligation imposed by, financial sanctions legislation, and the person committing the breach knew or had reasonable cause to suspect they were committing a breach. In addition, the Guidance also requires that one or more of the following be present: (i) the case involved a breach in which funds or economic resources have been directly provided to a designated person, (ii) there was evidence that a person had circumvented the applicable sanctions regime, (iii) a person has not complied with a requirement to provide information, or, without those factors being present, (iv) OFSI nevertheless determined that a penalty would be appropriate and proportionate. The last point in particular appears to give OFSI a significant amount of discretion in deciding whether to impose a penalty once it determines that a person has committed a breach of sanctions and knew or had reasonable cause to suspect they were in breach.

This minimum threshold is notably different from the enforcement of U.S. sanctions laws. Under U.S. law, civil sanctions violations are a strict liability offense (knowledge and wilfulness is only required in the criminal context). While knowledge is a factor that OFAC considers in deciding whether to impose a penalty and in determining the amount of the penalty, OFAC may impose a penalty even for what it considers non-egregious cases, where the person had no knowledge or reasonable cause to suspect they were violating sanctions.

Determination of Penalty Amount

If OFSI determines that the threshold for imposing a penalty has been crossed, it will decide an appropriate penalty level based on its assessment of the seriousness and estimated value of the sanctions breach. According to the Guidance, OFSI’s starting position will be the statutory maximum penalties under the Act, which for a breach relating to particular funds or resources is the greater of £1 million or 50 percent of the “estimated value of the funds or resources.” Neither the Act nor the Guidance specify whether OFSI calculates this maximum on a per transaction basis or whether it aggregates the value of a series of similar transactions. It is most likely that OFSI would make this determination on a case-by-cases basis. If OFSI considers each individual transaction that violates sanctions to constitute a separate breach, then a person violating sanctions may in certain cases be exposed to a potentially higher maximum penalty than under U.S. sanctions laws, where the civil statutory maximum per violation for the majority of sanctions violations is $289,238 or twice the value of the transaction, whichever is greater. Nevertheless, the Guidance emphasizes that OFSI’s response must be proportionate and reasonable.

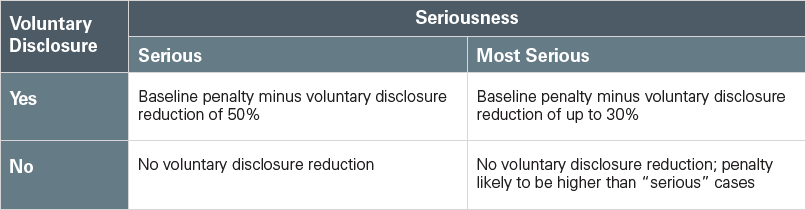

OFSI may, in most cases, reduce this maximum penalty by assessing the seriousness of the breach (including whether a case is “serious” or “most serious”) in light of the case factors listed above to arrive at a reasonable and proportionate baseline penalty. OFSI then applies the “penalty matrix” published in the Guidance:

The penalty matrix provides for up to a 50 percent reduction of the baseline penalty amount for persons who provide prompt and complete voluntary disclosure in “serious” cases, and up to a 30 percent reduction for voluntary disclosure in the “most serious” cases.

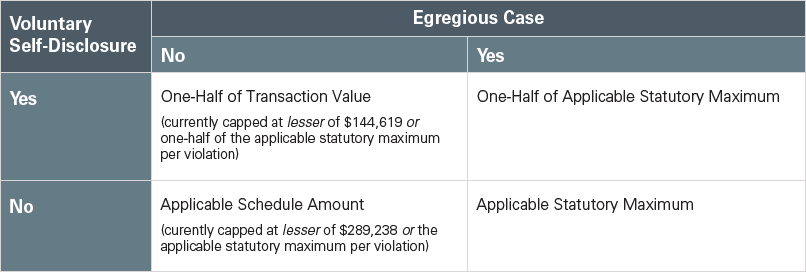

OFSI’s penalty matrix — specifically its emphasis on the seriousness of a breach and whether a breach was voluntarily disclosed — bears a striking resemblance to OFAC’s matrix for determining the base amount of civil penalties:

However, the penalty matrices serve slightly different purposes. OFSI uses the penalty matrix to adjust the baseline penalty (i.e., the statutory maximum may be adjusted downward, if appropriate, based on the case factors), while OFAC uses the penalty matrix to arrive at the base penalty, which may then be adjusted in either direction using the factors listed in the OFAC Enforcement Guidelines.

After using the matrix, the resulting amount is OFSI’s recommended, rather than final, penalty amount. The noncompliant party is entitled to make representations in response to the recommended penalty, which could change OFSI’s view on the amount of the final penalty or on whether a penalty should, in fact, be imposed. This again is very similar to OFAC’s Enforcement Guidelines, under which a person may respond to a prepenalty notice, which sets out OFAC’s preliminary assessment of the appropriate penalty amount.

Voluntary Disclosure and Information Reporting

Based on the Guidance, and consistent with the practice among other U.S. and U.K. regulators and prosecutors, a central feature of OFSI’s new enforcement approach is to encourage and reward voluntary disclosures. The Guidance explains that prompt and complete disclosure is considered a mitigating factor when OFSI is deciding whether or not to impose a penalty, and not just when OFSI is assessing a penalty amount in accordance with the penalty matrix.

Disclosures must be prompt and “materially complete on all relevant factors that evidence the facts of a breach.” OFSI will also look favourably on “early disclosure with partial information on the basis that the company or individual is still working out the facts and will make a further disclosure shortly.” In determining whether a disclosure is voluntary, OFSI will consider the facts and timing of each disclosure. If OFSI uses its authority to require the disclosure of information relating to a breach, it will not consider that disclosure to be voluntary.

OFSI’s emphasis on the disclosure’s voluntariness and completeness is in line with OFAC’s approach to voluntary disclosures, with some notable differences. OFAC does not give voluntary disclosure credit if a third party is required to and does notify OFAC of the violation or a substantially similar violation, or if a person submits a disclosure in response to an order or even a suggestion of another agency. This has resulted in many companies being denied significant voluntary disclosure credit after making large-scale disclosures that go well beyond the initial identification of a single or small number of violations by a third party. By contrast, the Guidance states that the mere fact that another party has disclosed first will not necessarily lead to the conclusion that later disclosure has any lesser value. The Guidance is silent as to whether a disclosure would be considered voluntary if another agency compels or suggests that disclosure is appropriate. Furthermore, while OFAC treats voluntary disclosures of non-egregious and egregious violations equally, OFSI will provide a lower penalty reduction for the voluntary disclosure of “most serious” breaches compared to “serious” breaches.

Public Disclosure

As a general rule and similar to the approach taken by OFAC, OFSI has said that it will publish the details of all monetary penalties. This practice increases the reputational risk associated with violations of U.K. sanctions. Nevertheless, these publications will likely be of important value for persons trying to avoid committing similar violations.

Conclusion

Compared to the provisions included in the Act, the Guidance sets out a more robust and structured enforcement approach for OFSI, and OFSI has reiterated that its new approach aims at promoting and enabling compliance, and responding to and changing noncompliant behaviour. However, it remains to be seen how far OFSI will embrace the practices of OFAC and other U.S. regulators in resolving sanctions violations, particularly in cases that involve parallel investigations or prosecutions in the U.S. and the U.K. In this regard, the Act and the Guidance provide for only limited judicial oversight of the operation of the regime, and Lord Justice (now Lord) Thomas’ concerns in the Innospec judgment, relating to the convergence of U.S. and U.K. enforcement practice in the absence of judicial oversight, bear reflection. We expect, nevertheless, that OFSI will embrace its new powers quickly and will soon take on an ambitious caseload.

___________________

1 See Skadden client alerts “The Policing and Crime Act 2017: Changes to the U.K. Financial Sanctions Regime” and “UK Establishes New HM Treasury Office to Implement Financial Sanctions.”

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.