With strengthened legislative mandates and significant regulatory reform in place, the U.S. government’s national security focus on protecting sensitive technology and data continues to gather steam. Although exactly what degree of trade and technology decoupling these efforts will ultimately seek to accomplish remains unclear, bodies such as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS or the Committee) and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) remain the government’s “tip of the spear.” Recent action by CFIUS and BIS, as well as pending action by both, highlight important ongoing issues for U.S. and foreign businesses and investors.

CFIUS: A Tale of Two Deals

A presidentially ordered divestiture. On March 6, the president ordered the Chinese company Beijing Shiji Information Technology to divest within 120 days the U.S. hotel-guest data firm StayNTouch, almost surely over concerns about the company’s access to hotel guest data. Highlighting the data-related concerns, the president’s order also required that Beijing Shiji immediately stop accessing hotel guest data through StayNTouch. Like many consumer-related businesses, StayNTouch software collects information from customers (in its case, hotel guests), including names, phone numbers, email addresses, credit card information, and the date and location of customers’ hotel stays. In addition, the software interfaced with some door lock vendors to enable virtual room keys, potentially creating an added national security risk beyond Chinese access to sensitive personal data.

The president’s order is the latest in an increasingly long line of matters centered on the sensitivity of data. Whether the required divestiture of PatientsLikeMe, Grindr or now StayNTouch, CFIUS continues to make clear that any acquisition by a Chinese acquirer of a U.S. company with significant data will face challenges. In the specific case of travel data, the broad use of such data by U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies — as well as an appreciation of how their Chinese counterparts could use the same information against U.S. targets — undoubtedly contributed to CFIUS’ concerns. For non-Chinese buyers, these concerns will likely be less acute, but heightened sensitivity to data issues remain, particularly if a non-Chinese buyer has deep connections to China or a history of data breaches or privacy-related regulatory infractions (whether with U.S. or other Western regulators). Thus both foreign and U.S. parties in a transaction should meticulously identify and understand the data involved, how it is protected from abuse and what additional steps might be necessary to assure CFIUS that the transaction does not produce new or aggravate existing data vulnerabilities.

A presidentially ordered block that didn’t materialize. According to recent press reports, CFIUS recommended to the president that he block the proposed acquisition of U.S. semiconductor company Cypress Semiconductor Corporation (Cypress) by its German counterpart Infineon Technologies AG (Infineon). However, just a few short days later, the story had reversed, with Infineon reporting that CFIUS has completed its review of the transaction and found no unresolved national security concerns — indicating that after an investigation, previous national security concerns had been mitigated through an agreement between the parties and CFIUS. Although there is no disclosure of what such mitigation might have involved, we expect it likely erected protections — along with third-party monitoring — around Cypress’ more specialized radiation-hardened products for satellites and other defense or aerospace applications.

CFIUS’ close scrutiny of the transaction highlights several risk factors that were likely at play. First, the Committee’s continued laser focus on the semiconductor and related industries was surely central to its review. Despite the relatively modest size of Cypress’ sensitive business, CFIUS reliably focuses more on national security sensitivities than any measure of a sensitive business’ financial materiality. Second, although a foreign investor’s CFIUS history is informative, it isn’t necessarily dispositive, and the sensitivity of a specific U.S. business is critical. Thus the approval of the Cypress acquisition — after the president had blocked Infineon’s proposed acquisition of Wolfspeed (which was narrowly focused on high-performance semiconductors) in 2017 — was not necessarily surprising. Finally, even when a buyer is not Chinese, CFIUS will always consider the buyer’s links to China. Thus the Committee likely closely examined Infineon’s various ties to China, including its joint venture with Chinese carmaker SAIC, as well as its significant operations in and revenue from China.

CFIUS: Regulatory Changes Continue

As forecasted by previous CFIUS rulemaking, which Skadden discussed most recently in a January 16, 2020, client alert, on March 4, 2020, Treasury proposed rules to formalize the adoption of CFIUS filing fees — designed in part to support expanded CFIUS staff and reviews.

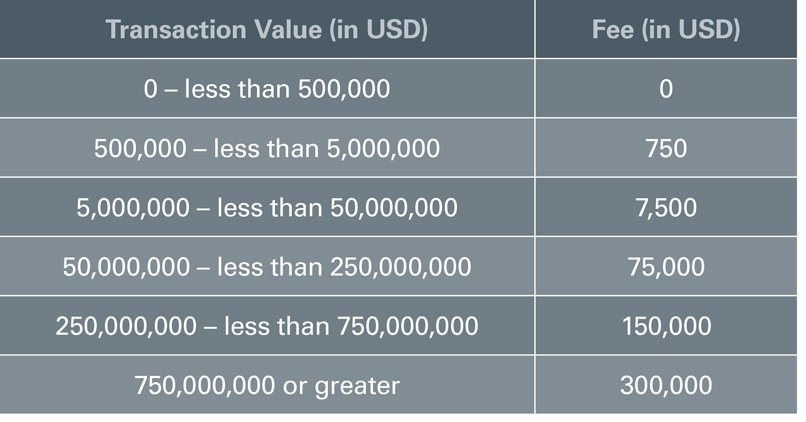

The fees range from $750 to $300,000, depending on the size of the transaction and are only required for the filing of a voluntary notice with the Committee — i.e., they are not required when filing a mandatory or voluntary short-form declaration, or in cases where CFIUS unilaterally initiates a review of a transaction (an “agency notice”).

Fees, which must be paid before CFIUS commences its review, are calculated based on the “value” of the transaction, meaning the total value of all consideration that has or will be paid by the investor. As the chart below indicates, the CFIUS filing fees will apply to all transactions valued at $500,000 or greater:

As CFIUS notes, these fees will not exceed .15% of the value of the transaction under the proposed structure, but the fees add another consideration to parties’ decision-making regarding whether to file with CFIUS and what form that filing should take. Although the lack of a fee for a short-form declaration adds a reason to file a declaration instead of a notice, parties should carefully assess whether filing a notice in the first instance for more complex transactions is prudent.

Perhaps even more consequential, new proposed rules reforming the mandatory declarations involving critical technology are also expected in the coming weeks. More specifically, we expect that one of the two prongs that make a declaration involving technology mandatory today — a U.S. business’ self-identified North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code — will be eliminated. As a result, we expect that a foreign investment in a U.S. business that produces export-controlled technology, regardless of what NAICS code applies to their business, would be the subject of a mandatory declaration if the investment is otherwise a controlling or covered investment.

Continuing Semiconductor Headwinds From Export Controls

Aside from CFIUS’ enhanced national security scrutiny of technology and data-related transactions, the semiconductor industry continues to face already implemented export control restrictions as well as a series of contemplated changes to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). In particular, the industry has suffered due to the addition of key Chinese customers, such as Huawei, to the Entity List, a restricted party list maintained by BIS in accordance with the EAR. Generally any item subject to the EAR requires a BIS license to be exported or reexported to a listed entity. While the industry has benefitted from a temporary general license pertaining to Huawei and certain industry participants reportedly have obtained specific licenses authorizing continued supplies to Huawei, the license has dramatically impacted the supply of U.S.-origin chips to Huawei.

Although the supply of U.S.-origin items to Huawei largely has ground to a halt, because U.S. semiconductor companies often engage in non-U.S. manufacturing, many have concluded that their non-U.S. made chips are not subject to the EAR and therefore may be supplied to listed entities such as Huawei. The U.S. government has become increasingly sensitive to what it perceives as the exploitation of certain loopholes that frustrate the intent of U.S. policy with respect to Huawei, among others. Accordingly, the U.S. government is actively considering certain changes to the EAR that would capture a greater number of items manufactured outside the United States within the scope of U.S. export controls.

One such proposal would amend the so-called de minimis rule by reducing the total percentage of U.S.-origin content that can be present in a non-U.S. manufactured item for it to be considered subject to the EAR from 25% to 10%. Another proposal would amend the so-called foreign direct product rule to capture items manufactured from the United States that are derived from any U.S.-origin technology within the scope of the EAR, as opposed to only such items that are derived from U.S.-origin national security-controlled technology. Both proposals, if adopted, would dramatically alter the scope of the EAR and could make it virtually impossible for the U.S. semiconductor industry to continue supplying to listed entities, such as Huawei, without an export license.

In addition to the de minimis and foreign direct product rules changes under consideration, BIS also reportedly may require licenses for the sale of tools used in the chip manufacturing process if those machines are used to produce components for HiSilicon, Huawei’s semiconductor subsidiary. Furthermore, reports indicate that BIS is considering applying more stringent controls generally on semiconductor manufacturing equipment, which potentially would trigger export licensing requirements for China writ large and not just for listed entities.

Finally, BIS currently is engaged in an effort pursuant to the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 to identify and subject to control certain emerging and foundational technologies, which will affect the semiconductor industry. Likely as part of the incremental roll out of these rules, BIS recently submitted a proposed rule to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), a statutory part of the Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President, for regulatory review to cover “Gate-All-Around Field Effect Transistor” (GAAFET) technology, which relates to semiconductor manufacturing.

Given the likelihood that BIS will implement some, if not all, of the above-described regulatory changes, the semiconductor and semiconductor equipment manufacturers would be well advised to undertake a rigorous review of their supply chains, including: (i) assessing whether U.S.-origin technology is being used to manufacture chips at overseas foundries; (ii) scrutinizing in the bill of materials chips that currently are supplied to or proposed to be supplied to listed entities or Chinese customers more broadly to ascertain what percentage of their content is derived from U.S.-origin components, as well as considering the availability of alternative component suppliers; and (iii) analyzing the potential financial consequences of the loss of listed Chinese entities or Chinese customers more broadly. Furthermore, for U.S. investors in the semiconductor industry, and in U.S. and Chinese companies in the semiconductor and other emerging technology industries, the regulatory risks associated with U.S. export controls regarding potential supply chain disruptions or the possibility of lost business should be top of mind.

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.