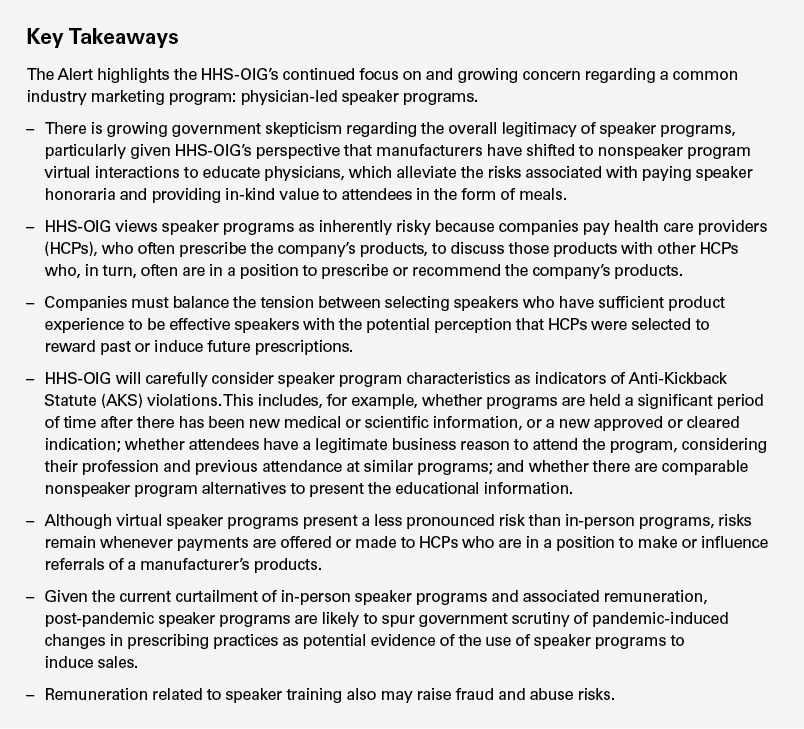

On November 16, 2020, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS-OIG) issued a Special Fraud Alert regarding the inherent fraud and abuse risks associated with manufacturer-sponsored speaker programs (Alert). The issuance of such an Alert, which happens infrequently, reflects the HHS-OIG’s long-standing concerns with what is arguably the highest-risk marketing practice in the life sciences industry, and HHS-OIG specifically acknowledges that the Alert is being issued during the COVID-19 pandemic emergency, which has curtailed many in-person activities. Although the list of “suspect” speaker program characteristics provided by HHS-OIG reflects misconduct cited in recent Department of Justice (DOJ) settlements, the Alert also questions the overall legitimacy of the number and content of speaker programs as an educational tool. Accordingly, manufacturers will need to carefully review their speaker programs and underlying needs justification process in light of HHS-OIG’s warning that it has “significant concerns” about any remuneration offered in connection with speaker programs and that all parties — including the manufacturer, speaker and attendees — “may be subject to increased scrutiny,” particularly if companies resume in-person speaker programs in the future.

Summary of the Special Fraud Alert

Risks Inherent in Speaker Programs

The Alert defines speaker programs as company-sponsored events at which a physician or other HCP makes a presentation to other HCPs about a product or a disease state on behalf of the company. Citing studies and its investigative experience, HHS-OIG observes that the provision of significant honoraria to speakers, who often are high prescribers, to speak in venues that are not conducive to learning or to speak to audience members who have no legitimate reason to attend indicates that at least one purpose of the remuneration to the speaker and attendees is to induce the HCPs to prescribe or recommend the company’s products.

In parsing the text of the AKS, HHS-OIG illustrates the fraud and abuse risks inherent in speaker programs: Companies pay HCPs, who often prescribe the company’s products, to discuss those products with other HCPs who, in turn, often are in a position to prescribe or recommend the company’s products. The Alert further underscores this inherent risk by cataloguing HHS-OIG’s prior guidance questioning the practice of manufacturers providing anything of value to HCPs in a position to make or influence referrals of the manufacturers’ products.1 The Alert also reflects HHS-OIG’s increased focus on the AKS implications of providing meals — especially expensive meals — and alcohol to speaker program attendees.

The Alert cautions that the remunerative features of speaker programs subject manufacturers, speakers and attendees alike to enhanced scrutiny, and provides an illustrative list of “suspect” characteristics that, “taken separately or together,” potentially signal that the speaker program violates the AKS:

- speaker programs with limited substantive information;

- a large number of speaker programs on the same or substantially the same topic or product, especially in situations involving no recent substantive change in relevant information;

- the continuation of speaker programs covering the same information or indication over long periods of time;

- speaker programs accompanied by an expensive meal or alcohol (with heightened concern for the provision of free alcohol);

- speaker programs held at a location that is not conducive to the exchange of educational information — including, according to HHS-OIG, restaurants;

- speaker programs attended by repeat attendees, prior speakers or attendees who don’t have a legitimate business reason to attend;

- sales or marketing department “influence” on the selection of speakers; and

- selection of HCP speakers or attendees based on their past or expected ability to generate company revenue, including the use of return on investment analyses to identify speaker program participants.

This list generally tracks conduct at issue in the recent Novartis settlement with the DOJ. As discussed more fully in our August 24, 2020, client alert on that settlement,2 Novartis admitted to a number of improper practices related to its speaker programs. In particular, the company hosted speaker programs with little or no educational content at expensive restaurants or venues that were not conducive to the serious exchange of clinical information, including sporting events and wine tastings. Novartis also hosted speaker programs repeatedly attended by the same HCPs or spouses, or other guests who were not HCPs. In addition, sales personnel were extensively involved in the nomination of HCP speakers.

To address these admissions, Novartis entered into an extensive corporate integrity agreement (CIA), which imposes strict limits and several novel obligations on Novartis’ speaker program. Although the Alert does not suggest that the wholesale adoption of the restrictive speaker program controls imposed in the Novartis CIA is required, the list of suspect speaker program practices identified in the Alert indicates that HHS-OIG will conduct a searching inquiry to ensure speaker programs are narrowly tailored to the purported justification for the programs, both at the outset and throughout the duration of the speaker program module.

Virtual Speaker Programs

HHS-OIG seizes upon the fact that some companies have transitioned to virtual speaker program formats to address pandemic social distancing practices to question whether companies should resume in-person programs given the availability of nonspeaker program alternatives. The Alert indicates that, on balance, HHS-OIG views virtual speaker programs as less risky, presumably because virtual programs eliminate risk factors associated with speaker program venues and reduces transfers of value to attendees in the form of meals and alcohol. However, the Alert cautions that risks remain “whenever” payments are offered or made to HCPs who are in a position to generate federal health care program business. This leaves open questions regarding the extent to which manufacturers can deliver food to HCPs in connection with virtual speaker programs and how that might impact the risk calculus.

Speaker Program Alternatives

HHS-OIG views the availability of means to provide HCPs with information about manufacturer products that do not involve remuneration to HCPs — such as online resources, the package insert, third-party educational conferences and medical journals — as further evidence that remuneration provided in connection with speaker programs is intended to induce or reward referrals. HHS-OIG appears to assume that these “less risky” alternatives can be as effective as legitimate speaker programs.

Implications for Pharmaceutical and Device Manufacturers

In-person speaker programs are one of the oldest and most common practices that manufacturers use to educate physicians and others about their products. Although the inherent risks associated with speaker programs are not new, the Alert questions the very legitimacy of speaker programs, and manufacturers should expect increased governmental scrutiny of their speaker programs, particularly if in-person programming resumes.

Because use of speaker programs to induce or reward referrals may be evidenced by the facts and circumstances surrounding such programs, the legitimacy of a company’s speaker programs will be scrutinized from multiple perspectives. The government will look not only to the amount of honoraria paid to HCP speakers but will also scrutinize internal communications, the structure and format of speaker programs and the company’s approach to program attendees.

Additionally, it is likely that during the pandemic — a time when in-person speaker programs have been curtailed or substantially reduced and the money spent by companies on those programs has similarly been impacted — the prescribing practices of speaker and nonspeaker physicians have changed. After the pandemic ends, counsel should expect close government scrutiny of both pandemic-induced reductions in speaker programs and current and post-pandemic product sales — particularly for products used to treat chronic disorders for which the fact of the pandemic does not impact the need for treatment — to assess whether a speaker program has been reinstituted solely to address a legitimate medical education need or was commenced anew in part to induce product sales.

Accordingly, it will be important for companies to demonstrate that the only purpose in hosting a speaker program was to provide timely and relevant educational information. In light of the Alert and recent settlements, we continue to encourage companies to consider certain compliance activities throughout the life cycle of a speaker program module:

- Needs Assessment. Companies should implement a rigorous, well-documented needs assessment process, which should undergo compliance review to ensure the number of speaker programs conducted is based solely on the need to educate HCPs on new products, new indications or other developments requiring updated information on the company’s products.

- Program Frequency. In conjunction with the aforementioned needs assessment, companies should carefully consider whether the number of programs, particularly on the same or substantially similar topic over an extended period of time, aligns with the ultimate goal of providing relevant and timely educational information to HCPs.

- Speaker Selection. Companies should institute objective criteria for selecting speakers, which must be met before sales or marketing personnel can nominate a HCP for consideration. Although having experience with a type of product may be one criterion for selection, companies should ensure that speakers are not selected based on prescribing habits alone. In addition, companies should ensure that any HCPs nominated by sales or marketing personnel are vetted and approved by members of the medical affairs and compliance departments.

- Attendee Credentials. Companies should consider imposing strict limits on the types of HCPs and HCP staff who can attend programs, with a focus on the types of attendees who have a demonstrable need for the information presented at a particular speaker program.

- Attendee Frequency. Companies should consider imposing strict limits on the number of programs (and over what time period within a given geographic area) an HCP, including HCP speakers, or a member of an HCP’s staff can attend. In addition to providing written guidelines, companies should consider utilizing automated systems that prevent HCPs and/or HCP staff from registering for the same or similar event during a specified time period.

- Venue and Content. Companies should ensure venues allow for the effective communication of educational information and that substantive information is presented during speaker programs. Companies also should consider if the food and beverage provided are appropriate for an educational seminar. It is important to scrutinize whether the provision of alcohol, particularly where it is free, will distract from the educational information presented.

- Fair Market Value. Companies should ensure they have a process to determine fair market value (FMV) for services provided by particular speakers, and that speakers are compensated in line with that analysis. This rigor should be applied to both speaker honoraria and speaker training payments, as the Alert notes that each may raise fraud and abuse risks. At the same time, it is important to remember that FMV analyses, alone, are insufficient to establish the legitimacy of speaker program payments. A payment made with the intent to induce a prescription or referral, or for services that are not supported by a legitimate business need — even if at a rate consistent with a company’s FMV analysis — is still improper.

Companies also should be cautious about modifying any compliance controls around speaker programs based on COVID-19 exigencies. As highlighted by the Alert, HHS-OIG has a long-standing concern regarding the practice of manufacturers providing anything of value to HCPs in a position to make or influence referrals of the manufacturers’ products. Given this concern, it is important for manufacturers to implement — and periodically assess the effectiveness of — robust controls around the development of annual speaker program plans, the selection of and payment to speakers, speaker program training, criteria for appropriate attendees, selection of venues, and in-kind transfers of value in the form of meals and alcohol.

_______________

1 See “OIG Compliance Program Guidance for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers,” 68 Fed. Reg. 23731 (May 5, 2003); “A Roadmap for New Physicians Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid Fraud and Abuse,” HHS-OIG, 22 (November 2010); “OIG Compliance Program for Individual and Small Group Physician Practices,” 65 Fed. Reg. 59434 (Oct. 5, 2000).

2 See, e.g., Skadden client alert, “Novartis’ $678 Million Settlement Sets Guideposts for Life Sciences Industry Speaker Programs” (Aug. 24, 2020); Stipulation and Order of Settlement and Dismissal, United States v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., 11-cv-0071 (PGG) (S.D.N.Y. July 1, 2020).

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.