A survey of recent rulings by judges from the bankruptcy courts for the Southern District of New York and the District of Delaware suggests that judges in these districts have very different views about the nature and extent of “consensual” third-party releases that may be approved in a given case. The data also indicates that their thinking on this issue continues to evolve as they confront new arguments.

The Bankruptcy Code allows a debtor to obtain a discharge of its debts upon confirmation of a Chapter 11 plan. The discharge does not affect the liabilities of third parties; however, Chapter 11 plans often contain releases for these third parties. Third-party release provisions, which are typically limited to claims related to the debtor, its business and/or the restructuring, are important currency and negotiating tools in Chapter 11 cases ensuring participation by other parties necessary for carrying out the plan.

The nondebtor parties involved in a restructuring want comfort that other third parties cannot bring certain claims against them. For example, debtor-in-possession and exit lenders typically insist upon third-party releases under a plan of reorganization. Similarly, officers, directors, creditors and other parties that provide a substantial contribution to a debtor’s restructuring often seek third-party releases in exchange for those contributions. Third-party releases also apply to related parties of releasees, such as affiliates, subsidiaries, officers, directors, attorneys, advisers and representatives.

Chapter 11 plans containing third-party releases were routinely approved in the past with little or no scrutiny unless challenged by an economic stakeholder in the case. More recently, however, the bankruptcy courts for the Southern District of New York and the District of Delaware have taken a closer look at such provisions. In general, these courts agree that third-party releases are binding to the extent that the creditors have consented to the releases (by, for example, voting to accept a plan including its releases or affirmatively opting to grant such releases). Accordingly, much of the debate has centered around what constitutes “consent” for purposes of granting third-party releases.

Recent decisions indicate that the judges in these districts have differing views on what constitutes “consent.” On the one hand, several judges have ruled that creditors or equity holders have consented to third-party releases if they do not “opt out.” In these instances, a creditor or equity holder typically receives a ballot, or a notice of nonvoting status in lieu of a ballot, which provides the opportunity to opt out. Those who do not check an opt-out election box and return the ballot or notice are considered to have granted consent for a third-party release. These judges reason that clear and conspicuous directions on the solicitation materials about how to opt out and the consequences of not doing so indicate that parties that do not take these steps have manifested their consent to the release. These judges also have looked at other factors when considering whether the releases are “consensual,” such as the importance of the releases to the restructuring; stakeholder support for the plan and the absence of objections; support by major parties in interest, including the official committee of unsecured creditors; the level of sophistication of the affected parties (e.g., whether they are institutional investors or general unsecured creditors); and how much the affected creditors were receiving under the plan.

On the other hand, some judges require stakeholders to affirmatively “opt in” to the third-party releases. These judges reason that inaction cannot be a sufficient manifestation of consent, especially since many creditors and equity holders receive little or no recoveries under the plan and may not appreciate that bankruptcy papers from a debtor could result in their release of claims against third parties.

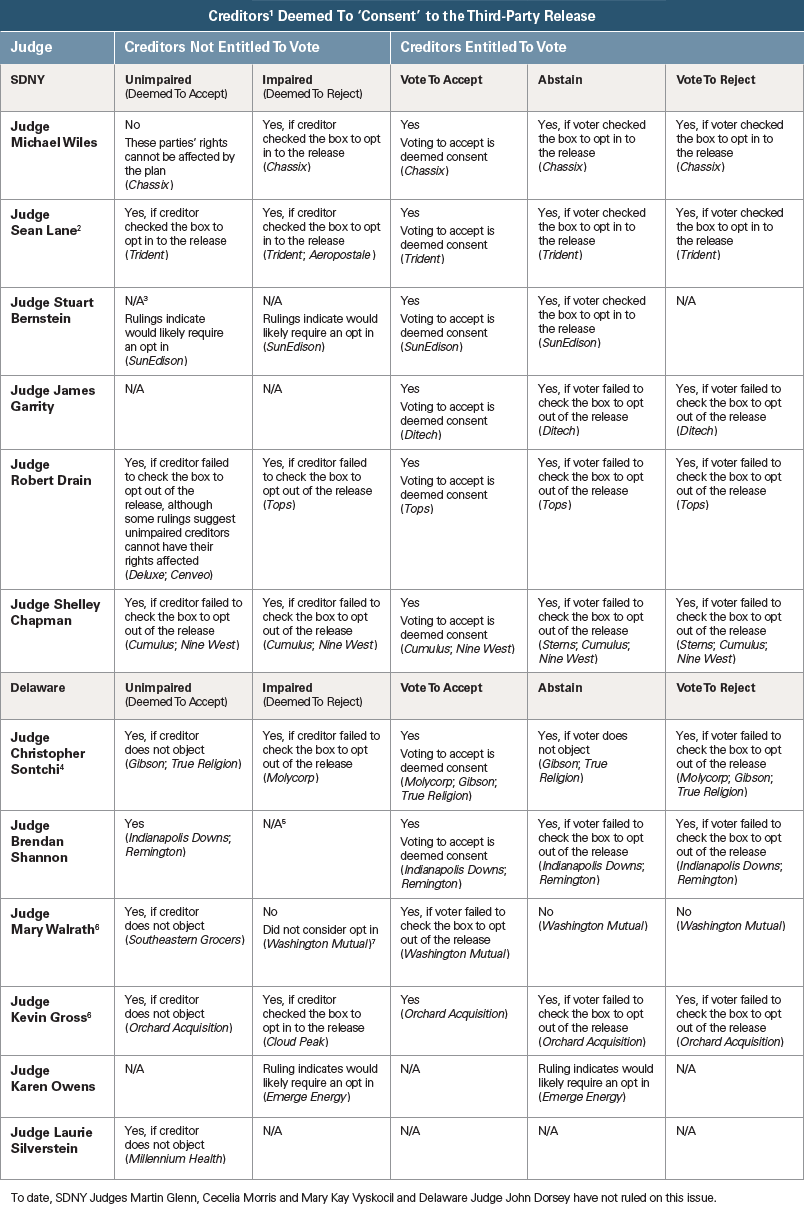

The following table provides an overview of how each judge has addressed the issue of what constitutes consent to a third-party release, to the extent that the judge has issued a ruling, whether published or orally from the bench. Some judges have indicated that what they may have approved in the past may no longer be justified in this constantly changing area of the law. In addition, most judges state that their rulings depend on the facts and circumstances of a particular case. Therefore, the characterizations set forth herein only provide general guidance on how a particular judge might rule when asked to approve third-party releases as consensual. (Notably, the table does not include orders approving third-party releases these judges may have entered without litigation or discussion of the issue because these provide less guidance on how a particular judge views consensual third-party releases.)

The table suggests that as judges take a fresh look at third-party releases, there will be a lack of certainty for parties regarding this key issue.

_______________

1 For purposes of this chart, references to creditors also include holders of equity interests.

2 After previously approving some Chapter 11 plans that provided for an opt-out mechanism, Judge Lane subsequently reversed course and recently indicated that he requires a greater manifestation of consent than that provided by an opt-out.

3 "N/A" indicates that the judge has not ruled on this issue.

4 In Molycorp, Judge Sontchi broadly approved the use of an opt-out mechanism for all voting and non-voting parties. Subsequently, in Gibson and True Religion, the judge clarified his position with respect to creditors that are unimpaired and deemed to accept the plan or receive a ballot and abstain from voting. For both of these creditors, Judge Sontchi has said that no opt-out mechanism is necessary, and it is a consensual third-party release if they are provided notice and do not object.

5 To date, Judge Shannon has not considered whether an opt-in or opt-out mechanism for parties deemed to reject would be sufficient. In all of the cases with rulings on the release issue, the plans did not attempt to release claims of parties deemed to reject.

6 Judge Walrath's decision in Washington Mutual is often cited to say that parties that abstain from voting cannot be deemed to consent to the third-party release. In Southeastern Grocers, Judge Walrath appears to have clarified this position by permitting a consensual third-party release by parties that receive notice and an opportunity to object to the plan and fail to do so. In that case, the parties were unimpaired creditors that were deemed to accept the plan; Judge Walrath has not considered this construct for unimpaired, deemed-to-reject creditors after Washington Mutual.

7 To date, Judge Walrath has not considered whether an opt-in mechanism for deemed-to-accept or deemed-to-reject parties would be sufficient.

8 In Orchard Acquisition, Judge Gross said that his thinking on consensual third-party releases had "evolved" since his prior orders confirming plans with these provisions but nevertheless approved the proposed third-party release in that case as consensual. To date, Judge Gross has not considered whether an opt-in or opt-out mechanism would suffice for deemed-to-accept or deemed-to-reject parties.

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.