Key Points

- Recent DOJ policies offer incentives for corporations to disclose possible criminal wrongdoing and cooperate in investigations. But companies cannot predict with certainty how they will be treated if they do so.

- The policies are intended primarily to hold companies and individuals accountable, including through disgorgement of profits and payment of restitution, rather than to secure more corporate convictions.

- The new policies increase pressure on companies to make rapid decisions about self-disclosures, typically before decision-makers know many of the facts.

- Legal and compliance departments need to prepare for the possibility of self-disclosing quickly and should have protocols in place for promptly investigating allegations of misconduct.

Over the past year, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has put a new emphasis on corporate accountability, and in particular, criminal accountability for individuals who participate in corporate crime. Beginning most significantly with a speech and memorandum from Deputy Attorney General (DAG) Lisa Monaco in September 2022, and continuing with two self-disclosure policy announcements in 2023, the department has highlighted expectations that companies self-disclose wrongdoing when they discover it.

The most recent pronouncements detail how the DOJ will consider reduced penalties where there have been:

- Prompt voluntary disclosures.

- Full cooperation in investigations.

- Disgorgement and remediation by the companies involved.

In her memo, DAG Monaco said that upcoming DOJ policies and procedures on self-disclosure and cooperation “should be sufficiently transparent such that the benefits of voluntary self-disclosure are clear and predictable.”

But a great deal of uncertainty still surrounds potential benefits of self-disclosure. Some of that is unavoidable. As Assistant Attorney General Kenneth A. Polite, Jr. stated in March 2023: “Every case is different, and our prosecutors need flexibility and discretion to apply their judgment in the myriad scenarios that may be presented.”

The uncertainty is heightened because of inconsistencies between recent DOJ self-disclosure policies, including one in January 2023 from the DOJ’s Criminal Division and a separate one in February 2023 for U.S. Attorneys’ Offices. The two branches combined handle the bulk of federal criminal prosecutions.

We have written previously about DAG Monaco’s statements and these two policies. (See our September 16, 2022, client alert, “Deputy Attorney General Monaco Announces Additional Measures Targeting Corporate Criminal Conduct: The Impact for Life Sciences Companies”; our January 19, 2023, client alert, “DOJ Doubles Down on Efforts To Incentivize Early Self-Reporting and Cooperation”; and our March 3, 2023, client alert, “DOJ Implements Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy for US Attorneys’ Offices.”)

In this article, we discuss the new policies’ aim and how companies can navigate them when faced with potentially criminal conduct by employees or agents.

A Decline in Corporate Prosecutions

The DOJ has made clear that it believes unreported corporate crime remains a major problem despite past efforts encouraging self-disclosure: The U.S. Sentencing Guidelines offers benefits for self-disclosure, and large potential financial incentives are available for whistleblowers. From the DOJ’s standpoint, corporate crime can be extraordinarily difficult to identify, investigate and successfully prosecute.

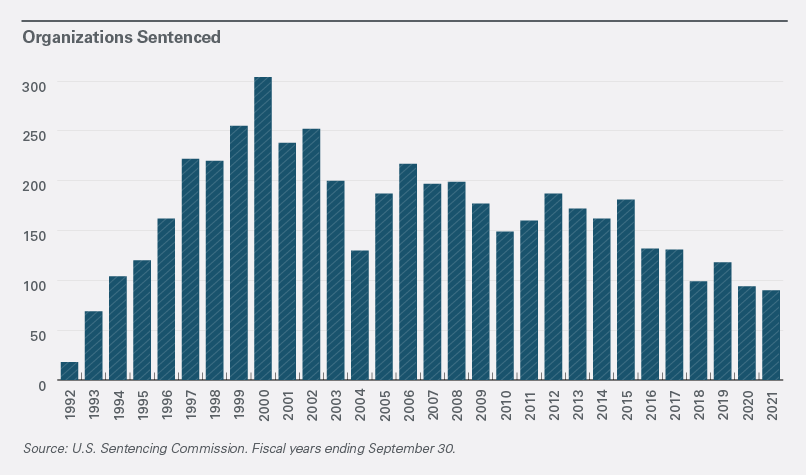

A 2022 U.S. Sentencing Commission report shows the decline in recent years of prosecutions of companies through conviction and sentencing. Surveying 30 fiscal years ending in 2021, the commission found that the number of organizations that have received a federal criminal sentence has dropped 70% since 2000.

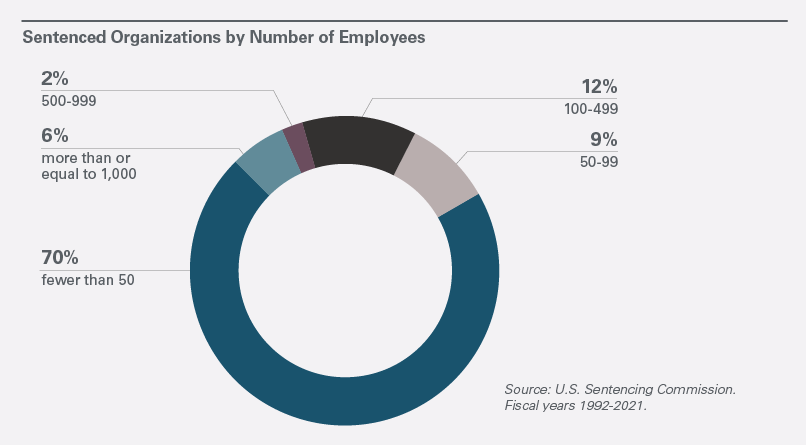

Moreover, the companies that are prosecuted and sentenced tend to be small. Most (70.4%) had fewer than 50 employees. Less than 10% (8.1%) had more than 500 employees. The overwhelming majority were privately held (92.2%).

There are various possible explanations for the decline:

- A reorientation of law enforcement resources toward national security after the September 11, 2001, attacks.

- The use of alternatives to prosecution, particularly for larger companies.

- Potentially, a decrease in corporate crime itself.

The limited prosecutions of large companies may also reflect concerns within the DOJ about disproportionate collateral consequences, particularly following the 2002 conviction of Arthur Andersen stemming from its role as auditor for Enron Corp. Though later overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, the conviction contributed to the accounting firm’s collapse.

The new self-disclosure policies are not designed to increase the number of companies that are convicted and sentenced. They are in place to increase the number of companies that are held accountable for misconduct by requiring, among other things, disgorgement of profits and full restitution to victims.

The policies are also motivated in large part by a concern that, while company shareholders might pay a price for corporate misconduct, the individuals who engage in the misconduct often are not held accountable.

By increasing pressure on companies to self-report misconduct and fully cooperate with investigations, the DOJ hopes to build more, and more effective, cases against individuals. The department has emphasized that its “first priority in corporate criminal matters is to hold accountable the individuals who commit and profit from corporate crime,” and the new policies do not include benefits for individuals.

Challenges in Responding to the New Policies

Different Approaches Within the DOJ

The Criminal Division’s and U.S. Attorneys’ Offices’ policies describe similar requirements to receive the benefits they propose (early voluntary self-disclosure before an imminent threat of disclosure by a third party; full cooperation in an investigation; and disgorgement and payment of restitution).

However, the policies differ significantly in the maximum benefit they describe.

- The Criminal Division’s policy states that, when a company has met all the division’s standards, there will be a presumption that a company will receive a “declination” absent aggravating circumstances. In other words, DOJ expects that it would not pursue charges against the company, although it would publicly disclose the declination.

- In contrast, the U.S. Attorneys’ Offices’ policy states that, when a company has met all its standards, a U.S. Attorney’s Office will not seek a guilty plea absent aggravating circumstances. The office may, however, seek a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) or nonprosecution agreement, both of which typically involve significant financial penalties. When a U.S. Attorney’s Office seeks one of those alternative resolutions, the penalty generally will not exceed 50% of the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines range.

Neither policy guarantees those outcomes. Both retain the flexibility to offer less than the maximum benefit when prosecutors decide that circumstances warrant it. Likewise, neither defines the “aggravating circumstances” that tip the scales against the maximum benefits.

Instead, the policies provide a nonexhaustive list of factors prosecutors will consider in determining whether there are aggravating circumstances, including the pervasiveness of misconduct within the company and executive management’s involvement in the misconduct.

The U.S. Attorneys’ Offices’ statement that they may insist on a DPA even if a company has met the self-disclosure, cooperation and remediation standards suggests that the offices could put less of a premium on those activities than the Criminal Division.

Ongoing Requirements in DPAs

While DPAs do not involve a plea, they are often more attractive to prosecutors than convictions because they can involve steep penalties and a series of commitments for compliance improvements — with accompanying years-long reporting requirements — without the potential collateral consequences of convictions that can negatively impact companies.

For example, in January 2021, the Criminal Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Texas entered into a DPA with Boeing Company resolving a criminal charge related to a conspiracy to defraud the Federal Aviation Administration involving Boeing’s 737 MAX airplane. Boeing agreed to pay over $2.5 billion, which included a fund to compensate the heirs, relatives and legal beneficiaries of passengers who died in two Boeing 737 MAX crashes.

Among other conditions, Boeing agreed to improve its compliance program and to meet with the DOJ quarterly for the DPA’s three-year term to report on those improvements. The DOJ entered that DPA rather than pursue a conviction, even though Boeing did not self-disclose the conduct at issue (and therefore would not have met the standards in the new policies).

Time Pressures

The policies generally do not afford companies the benefit of time to investigate allegations sufficiently to determine their veracity before self-reporting. Companies that wish to pursue benefits under the policies will often have to make decisions quickly and with limited facts.

In order for the company to get credit under the new policies, any self-disclosures must include all relevant facts known to the company at the time. Follow-up requests from the DOJ can easily send the company’s own investigations into new and time-consuming directions.

Recommendations

Even though they do not prescribe clear and predictable outcomes, the new policies provide important guidance that companies should consult whenever they receive a credible report that an employee or agent might have broken the law. The policies describe prosecutors’ standards and expectations for a company to receive significant benefits, even where lacking guarantees.

Legal and compliance departments should include in their protocols consultation of the policies whenever they receive a report of potentially unlawful conduct. They should also ensure there are guidelines for preserving all potentially relevant data and launching an internal investigation with appropriate resources.

In addition, companies should have a communications plan in place for discussions about possible self-disclosures on short notice and with limited facts, rather than working out those procedures for the first time when reacting to a new allegation. Decisions not to disclose can always be revisited, but companies likely will not get full credit under the policies if someone else first reports the misconduct to the DOJ.

As was the case before the new policies, companies will need to consider self-disclosure on a case-by-case basis. As the policies substantiate, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for companies.

Finally, companies should monitor new cases. The DOJ will seek to highlight aspects of its policies in upcoming resolutions with companies, even though the investigations may have started before the policies were announced. Those outcomes should provide insight into the DOJ’s new approaches and factor into companies’ decisions on how to handle new allegations of illegal activity.

See all of Skadden’s April 2023 Insights

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.