For the first time since China’s Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) came into force in 2008, the government is proposing major changes to its centerpiece antitrust legislation. On January 2, 2020, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) published a draft amended Anti-Monopoly Law for public comments (Draft AML). The key changes in the Draft AML include proposals to:

- dramatically increase fines, especially for (i) failures to notify mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures, (ii) gun-jumping, and (iii) breach of merger conditions; and

- introduce mechanisms to stop the review clock during merger control assessments by SAMR.

The Draft AML would also articulate a more precise definition of “control” for evaluating notifiability of potential transactions, and add an indispensability requirement for the use of efficiency defenses. The Draft AML is still subject to consultation and further review by China’s administrative and legislative bodies. While there is no fixed timetable for formal adoption, the Draft AML could be passed by the National People’s Congress as early as 2021 if the remaining process runs smoothly.

Significant Increases on Maximum Fines for Antitrust Violations, Particularly Failures To Notify Qualifying Mergers, Acquisitions and Joint Ventures

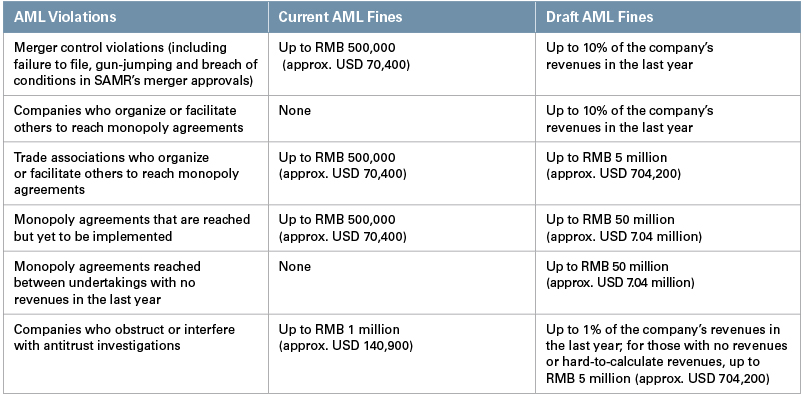

In its 11 years of antitrust enforcement, China’s agencies have collectively imposed fines of only RMB 12 billion (approximately USD 1.7 billion), lagging far behind penalties levied by peer agencies and regulators in the U.S. and Europe. One of the most criticized provisions of the current AML (at least domestically in China) has been the very low statutory maximums for monetary penalties, especially for failures to file mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures that meet the notification thresholds for mandatory SAMR review. The Draft AML proposes to significantly increase the level of fines for such failures to file. It would also raise the statutory maximums for other conduct-related behavior. The following table sets forth a comparison between the Draft AML and the current AML:

Adds a ‘Stop the Clock’ Mechanism in Merger Reviews

SAMR’s current merger review process requires longer review times for complex, cross-border mergers and acquisitions than review times for similar transactions in almost any other jurisdiction. Transactions with significant competition concerns and industrial policy implications can spend over a year in review, especially when SAMR faces pressure from strategic stakeholders in China who may opportunistically attempt to use the review process to extract commercial or political concessions from the parties.

The Draft AML preserves the same statutory review periods, but proposes to introduce a stop-the-clock mechanism that would allow SAMR to pause its examination of a notified transaction, potentially leading to even greater timing uncertainty given the already challenging review timelines. Article 30 of the Draft AML would propose to stop the review clock whenever:

- the notifying party applies or agrees to suspend the review clock;

- the notifying party is requested by the AML enforcement agency to supplement additional documents or information; or

- the notifying party is negotiating remedies with the AML enforcement agency.

Such a mechanism would provide SAMR even more timing flexibility in its review process. For example, for the vast majority of transactions requiring remedies in China, SAMR not only takes the full review period but also requires the parties to “pull and refile,” effectively restarting the review clock at zero. Thus, for transactions under review in the Ordinary Procedure,1 the timeline begins with a “completeness review” period of typically four to eight weeks, followed by Phase I (30 calendar days) and Phase II (90 calendar days). Phase II can be extended by an additional 60 calendar days (and is sometimes colloquially referred to as Phase III).

For complex cases, especially those where remedies may be required for approval, parties that are yet to reach a resolution with SAMR when the clock of the 60-day Phase III period is running out are often required to “pull-and-refile” their cases for review, restarting the clock at the beginning of Phase I. Nearly every conditional decision issued by SAMR in the last three years has required at least one such “pull-and-refile” and some have required multiple cycles through the review. For example, in 2019, SAMR’s review of a proposed joint venture between Zhejiang Garden Bio-Chemical High-Tech and Royal DSM lasted 554 days, setting a new record for China’s longest review period since merger control was introduced in 2008.

Currently, parties must theoretically consent both to enter into Phase III and to pull-and-refile (as the AML currently provides for a deemed approval if Phase II or Phase III expires without either an approval or prohibition from SAMR). While withholding consent is ordinarily not a practical option for parties under review, it does give the parties some statutory leverage to pressure SAMR to accelerate review to the maximum extent possible. Under the Draft AML, however, SAMR will simply be able to toll the review clock — especially during the negotiation of remedies — eliminating even the nominal restraint that exists under the current AML. This could in turn lead to a more challenging negotiation for companies to reach a timely resolution with SAMR as this mechanism will only further insulate SAMR from statutory time pressure.

In addition, the Draft AML would also allow SAMR to stop the clock when it has requested the parties “to supplement additional documents or information.” Many other jurisdictions already have similar mechanisms, and in practice these devices are very commonly used by regulators to slow a review when the regulator is understaffed or has other timing concerns unrelated to the review of the particular transaction. This leads to the issuance of superfluous requests for information simply as a means to gain more review time. Given the chronic understaffing of the merger review divisions at SAMR, as well as the large number of reviews, adding such a mechanism could potentially lead to additional, largely unnecessary information requests –– for both complex and noncomplex cases –– if SAMR does not exercise caution in its use.

Defines ‘Control’ in Merger Reviews

Under the current AML, mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures that lead to a change of “control” must be notified for SAMR’s approval before they are allowed to close, assuming the revenue thresholds are otherwise met. The concept of “control” is a term of art in the antitrust context, and can be broader than its usage in the ordinary business sense. Thus, as recognized in other jurisdictions such as the European Union, control in the antitrust context may adhere not only where a company holds a majority of the voting rights or capital interest or can appoint a majority of the board of directors, but also where a minority stake or even a contractual relationship confers “decisive influence” over a target’s strategic operations. As provided in Article 3 of SAMR’s Guidelines on Notifying Concentration of Undertakings, this might happen where, for example, a minority investor receives unilateral veto rights over such matters as appointment or removal of senior management, approval of the annual business plan or budget, or approval over major transactions.

While the current AML uses the term “control,” the statute itself lacks any definition of the word. Article 23 of the Draft AML would elevate the definition of “control” into an enacted law, stating that “control” means the right to have, or actual state of having or potentially having, either solely or jointly, a direct or indirect influence on decisions regarding production, operation and other undertakings.

Nevertheless, the Draft AML does not further elaborate with any specificity on when joint venture parents or minority investors might acquire “control.” Without the publication of additional guidelines, it appears that SAMR still intends to preserve ultimate discretion in determining the notifiability of those transactions, at the expense of providing clear guidance to help companies anticipate and navigate such issues in advance.

Adding an Indispensability Requirement in the Demonstration of Efficiency Exception for Monopoly Agreements

With regard to monopoly agreements, the current AML takes an “illegal unless excepted” approach; that is, a prescribed conduct is illegal unless the agreement meets one of the specifically enumerated efficiency exceptions in the AML, such as improving product quality, saving production costs, or enhancing the competitiveness of small and medium-sized businesses. While the Draft AML preserves these existing efficiency defenses, Article 18 of the Draft AML would limit application by also requiring a company to prove that the agreement is indispensable for achieving the specified efficiencies. This will raise the bar on using such efficiency exceptions as a defense for future SAMR investigations

Conclusion

Based on the notice on the 2020 Legislative Work Plan that SAMR published on March 17, 2020, the AML amendment and the amendment to the Interim Provisions on the Review of Concentration of Undertakings (the Merger Review Rules) are the two major legislative pieces on which the Anti-Monopoly Bureau of SAMR is focusing in 2020. While there is no concrete timetable for the promulgation of the amended AML, a draft of the revised Merger Review Rules is expected to be published for public comments in June of this year, as SAMR wishes to issue the revised set of rules by the end of 2020. SAMR may also be considering an increase to its merger filing thresholds (which have not been increased since introduction in 2008).2 This would hopefully help improve review times by reducing the current caseload, which strains SAMR’s limited resources for review.

Although the Draft AML remains only a draft at this point, it constitutes a significant step for China as the first proposed amendment to the landmark AML, and is bound to have significant impacts in the foreseeable future. The changes in the Draft AML reflect the current thinking of the regulator and provide a helpful guide for companies to better predict the future antitrust enforcement — most crucially, the proposed increased financial penalties for failures to notify required transactions signal SAMR’s commitment to continue to ramp up its (already active) enforcement in this area, while the stop-the-clock proposal will be seen as removing one of the few, even nominal, leverage points that parties have during merger review. As SAMR continues to use its merger control reviews both to identify and resolve competition concerns as well as to safeguard the national economic development of China, the Draft AML provides important tools that will help further protection of domestic interests.

_______________

1 In contrast to the Simplified Procedure, which is generally only available for noncomplex cases and likely will not be materially affected by such a “stop-the-clock” mechanism.

2 Currently, the thresholds are set that in the last completed fiscal year: i) the total worldwide turnover of all parties to the transaction exceeded RMB 10 billion (approx. USD 1.4 billion), OR ii) the combined Chinese turnover of all parties to the transaction exceeded RMB 2 billion (approx. USD 285.7 million); AND the Chinese turnover of each of at least two parties to the transaction exceeded RMB 400 million (approx. USD 57.1 million).

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.