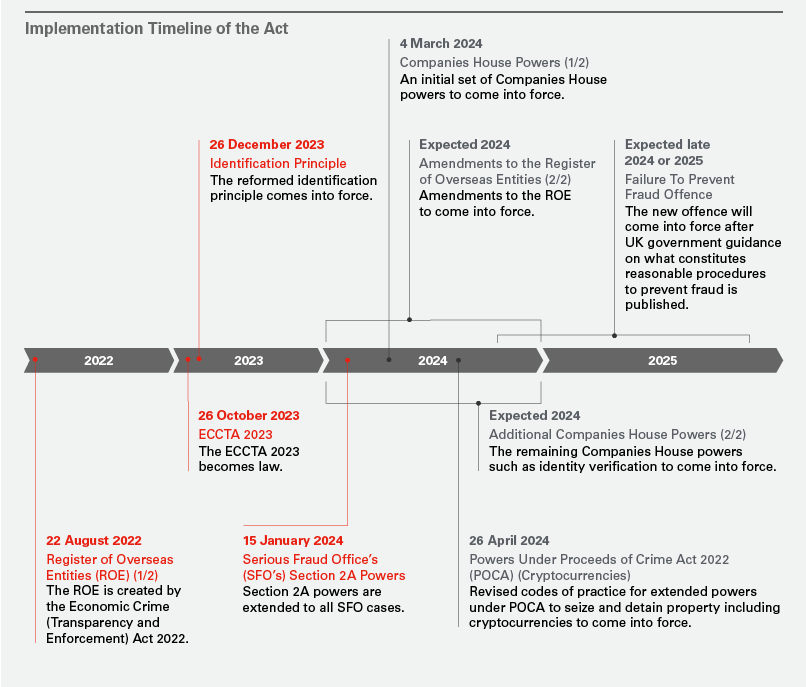

On 26 October 2023, the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (the Act) became law in the UK. The Act represents a major overhaul of the UK government’s framework for tackling financial crime and has brought into force a number of significant changes.1 Below we have set out the key changes that are now in effect, together with other provisions that are due to be implemented and which will impact corporates in the UK.

1. Expansion of the Identification Principle

Under the former framework, corporates could only be prosecuted for criminal offences if it could be shown that an individual acting as the “directing mind and will” of the corporate had the requisite state of mind (such as intention, recklessness or dishonesty) for the offence (the identification principle).2 Historically, this made it challenging for authorities in the UK to successfully prosecute corporates, particularly large corporates with complex management systems that make it difficult to identify whether an individual belongs to the “directing mind and will” of the entity.

The Act has expanded the identification principle so that a corporate will be guilty of certain criminal offences, including bribery, tax, money laundering, fraud and false accounting offences,3 if the offence is committed by a “senior manager” acting within the actual or apparent scope of their authority. A “senior manager” is someone whose role includes:

- Making decisions regarding how the whole or a substantial part of the corporate’s activities are to be managed or organised.

- Actively managing or organising the whole or a substantial part the corporate’s activities.

The reform means that the actions of a wider pool of senior executives can be attributed to a corporate for the purposes of establishing criminal liability against it. The explanatory notes of the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007, from which the notion of “senior management” was borrowed, indicates that this will likely cover those who are in the direct chain of management and those who are in strategic or compliance roles. This may include company directors, senior officers who are not board members, and potentially individuals in departments such as HR, in-house lawyers, and regional or division managers in national organisations.4

2. Failure To Prevent Fraud Offence

The Act introduces a new strict liability criminal offence modelled on the “failure to prevent” offences that have previously been introduced in the UK, such as failure to prevent bribery and the facilitation of tax evasion. Under the failure to prevent fraud offence, a corporate will be held liable if it fails to prevent a set of specified fraud offences being committed by an “associated person.”5

The new offence applies only to “large” organisations and exempts small and medium-sized corporates. A corporate will be deemed a “large organisation” under the Act if two or more of the following conditions are satisfied in the financial year preceding the year in which the alleged fraud is said to have occurred: The company has (i) more than 250 employees, (ii) turnover of more than £36 million, and/or (iii) a balance sheet total of more than £18 million.

A parent company of a group is only a “large organisation” if it meets at least two of the following criteria: (i) an aggregate turnover of more than £36 million (or £43.2 million gross), (ii) an aggregate balance sheet total of more than £18 million net (or £21.6 million gross), and/or (iii) more than 250 aggregate employees.

An “associated person” includes employees, agents, subsidiaries or any person who otherwise performs services for or on behalf of the corporate. This broadly follows the format of how an associated person is defined under other UK anti-corruption legislation. Parent companies can therefore be held liable for fraud committed by an employee of a subsidiary if the employee holds the requisite intent. The associated person must intend to directly or indirectly benefit from either the corporate or a person to whom services are provided on behalf of the corporate.

Two defences are available, namely where: (i) the corporate was the intended victim of the fraud, or (ii) the corporate can demonstrate that it had reasonable fraud prevention procedures in place, or that it was reasonable not to have such procedures. The Act does not define what reasonable fraud prevention measures would entail, however we expect that a principle-based approach will be taken mirroring the failure to prevent bribery and facilitation of tax evasion offences.6

The location of the corporate and its associated persons does not matter — a corporate will be held liable if it has failed to prevent one of the specified fraud offences. A Government Factsheet on the Act states that ‘‘if an employee commits fraud under UK law, or targeting UK victims, the employer could be prosecuted,” even if the corporate and the employee are based overseas.7 If held liable, a corporate can receive an unlimited fine.

3. Crypto-Related Enforcement

The Act expands the powers available to law enforcement in respect of crypto-related criminal activity. This includes extending the confiscation and civil recovery regime under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA) to cryptoassets, making it easier for law enforcement to seize, freeze and recover cryptoassets that are connected to illicit or criminal activity, as well as, for example, introducing powers to convert crypto assets into money before a forfeiture hearing.

Given that certain powers envisaged under the Act require amendments to POCA, a draft set of regulations titled Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Search, Recovery of Cryptoassets and Investigations: Codes of Practice) Regulations 2024 was published on 23 January 2024. In short, these regulations aim to:

- Introduce revised codes of practice for (i) powers under POCA to seize and detain property, including cryptoassets and related items, and (ii) investigation powers of certain officers under POCA Chapter 2, Part 8, including unexplained wealth orders.

- Introduce a new code of practice relating to the powers of certain officers under POCA, Part 5 to search for, seize and detain cryptoassets and related items.

- Revoke the previous codes of practice under POCA on these topics.8

These reforms are also expected to have implications on a number of cryptoasset-related businesses such as cryptoasset service providers and exchanges who may be required to comply with court orders to assist law enforcement in seizing cryptoassets.

4. SFO Powers

The Act has also reformed and extended the Serious Fraud Office’s (SFO) pre-investigative Section 2A powers, so called due to the Criminal Justice Act 1987, which, in addition to creating the SFO, at Section 2, also granted the agency’s primary investigative tools.

The former Section 2A powers permitted the SFO to compel individuals and companies to provide information at a pre-investigation phase in suspected cases of international bribery and corruption where there were “reasonable grounds to suspect” that a crime had taken place. The Act has now extended this to all potential SFO cases so that these powers may be used in cases such as suspected fraud or domestic bribery or corruption, which were previously excluded. In particular, under Section 3(5) of the Criminal Justice Act 1987, the SFO has an existing power to share information it obtains using its compulsory powers with other agencies, and can therefore share information it has obtained under its newly extended section 2A powers even if the receiving agencies do not possess equivalent pre-investigative powers.

5. Companies House Powers

Building on the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022 (the 2022 Act), the Act introduces new powers for Companies House to enhance its role in combatting illicit wealth. Companies House has confirmed that a number of provisions of the Act will come into force in March 2024 including:

- Enhanced powers to query information submitted to or already on the Companies House register, and challenge filings where it identifies information that is potentially fraudulent, suspicious or might otherwise impact the integrity of the corporate register or wider business environment.

- A new requirement to submit a registered email address and confirmation that the company has been created for a lawful purpose.

- Information sharing powers to allow the body to proactively share data with law enforcement, regulators and other public authorities.

The Act also introduces increased obligations to verify the identities of people with significant control (PSCs) and other individuals or entities filing on behalf of a company on the register, and strengthens the existing offence under Section 1112 of the Companies Act 2006 for companies that deliver false or misleading statements to Companies House.

These powers will require secondary legislation in order to come into force. To date, no set of draft regulations has been identified for this purpose, however, an initial set of powers identified above has been slated for implementation on 4 March.9 Other provisions of the Act, such as identity verification, have been confirmed by Companies House for implementation at a later date.

6. Register of Overseas Entities

The 2022 Act introduced a new Register of Overseas Entities detailing the beneficial ownership information for foreign entities that are registered proprietors of certain interests in land in the UK. The Register of Overseas Entities came into force on 1 August 2022 and has been further updated by the Act.

The Act makes two principal changes: (i) it expands the scope of registrable beneficial owners for the purposes of the Register of Overseas Entities, and (ii) it increases the additional information that must be delivered to Companies House. In relation to (i), this change has been introduced largely to address the criticism that the 2022 Act did not go far enough. The 2022 Act required foreign entities holding UK land as nominee for another to register its beneficial owners with Companies House. This was criticised because it did not capture the beneficial owner of the person who the foreign entity acted as nominee on behalf of. If a foreign entity is holding UK land as nominee for another, it will not only have to register its beneficial owners, but also those of the true beneficiary. The Act has also introduced additional requirements related to where a foreign entity acts as trustee in holding UK land.

These provisions have not yet taken effect, but we expect they will come into force this year.

7. Related SFO Developments

Together these reforms under the Act are set to enhance the UK government’s armoury in tackling financial crime, including by making it easier to attribute certain economic crimes committed by employees to the corporate employer. To this effect, in his first public speech delivered earlier this month,10 the new director of the SFO Nick Ephgrave announced his intention for the SFO be the first authority in the UK to use the “great new tools” the Act has introduced to bring a successful prosecution.

As part of his speech, the director of the SFO also announced his vision for a “bolder, more pragmatic, more proactive” SFO that is swifter in its approach, unafraid to launch more dawn raids, and makes use of tools such as technology assisted review to accelerate and make its disclosure processes more efficient. Currently, disclosure consumes around 25% of the SFO’s operational budget, and the agency has suffered several high-profile disclosure failures that have led it to abandon prosecutions. The SFO director also suggested the creation of economic incentives for whistleblowers who come forward with information on corporate wrongdoing — if this were to be implemented, it would represent a radical departure from the UK’s current non-remunerative approach.

8. Conclusion

In light of these significant changes, corporates should review existing policies and procedures to determine whether they are adequate to address and identify fraud and economic crime-related risks, as the Act widens the range of offences and situations that will be attributable to corporate employers. This will also be an important part of establishing adequate fraud prevention measures on which UK government guidance is pending. Corporates may also wish to identify potential “senior managers” or “associated persons” who could be within scope of the new rules, and implement training so that employees are able to identify and report behaviour that could lead to corporate liability under the reforms.

_______________

1 The Act builds in part on the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022, which sought to make it easier to identify and trace illicit wealth in money laundering and economic crimes. See our previous alert on this topic, “New UK Economic Crime and Transparency Laws Take Effect,” 26 April 2022.

2 An exception to this rule was the failure to prevent offences included in the Bribery Act 2010 and Criminal Finances Act 2017.

3 These are known as “relevant offences” and are listed at Schedule 12 of the Act. The listed economic crimes also include conspiracy to commit a listed economic crime, or aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the commission of such a crime. It is expected that the list of crimes that are within scope of the Act will be extended, and an express power has been granted to the secretary of state to modify this list on an ongoing basis.

4 To this effect, see the Ministry of Justice’s Guidance for the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007.

5 The specific fraud offences are: fraud by false representation, failing to disclose information or abuse of position (ss2-4 Fraud Act 2006); obtaining services dishonestly (s11 Fraud Act 2006); participating in a fraudulent business (s9 Fraud Act 2006); false accounting (s17 Theft Act 1968); false statements by company directors (s19 Theft Act 1968); fraudulent trading (s993 Companies Act 2006); cheating the public revenue (common law); or aiding and abetting, counselling or procuring the commission of one of these offences.

6 The six principles would therefore be: (i) proportionate procedures, (ii) top level commitment, (iii) risk assessment, (iv) due diligence, (v) communication (including training) and (vi) monitoring and review.

7 See “Factsheet: Failure To Prevent Fraud Offence,” updated 26 October 2023.

8 The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Search, Seizure and Detention of Property: Code of Practice) Order 2018, SI 2018/8 and the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Investigations: Code of Practice) Order 2021, SI 2021/726.

9 See “First Changes to UK Company Law Expected on 4 March,” 22 January 2024, Companies House.

10 See “Director Ephgrave’s Speech at RUSI,” 13 February 2024, Serious Fraud Office.