Key Points

- In light of the vigorous enforcement of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, boards in their oversight role should ensure that their companies conduct heightened diligence on their supply chains, including upstream suppliers.

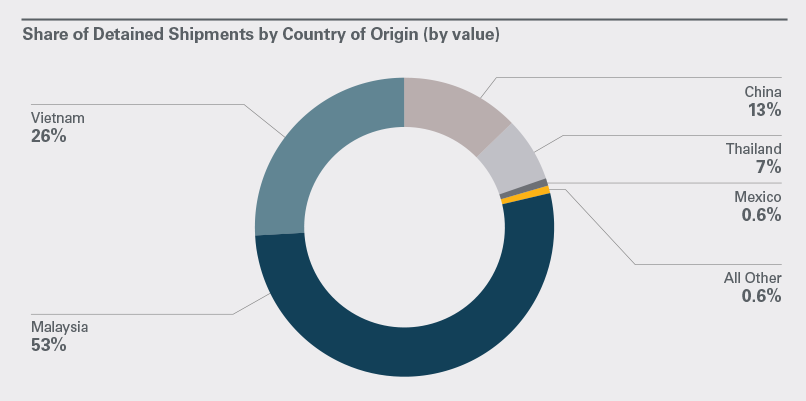

- Industrial products and components increasingly are targets — not just items traditionally seen as high risk from a forced labor standpoint, such as textiles and solar panels — and the vast majority of shipments detained have countries of origin other than China.

- The U.S. government pays close attention to NGO and other reports on products that may contain components made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang region.

- The U.K., Germany and Canada have implemented their own forced labor prevention laws, and the EU is considering one.

The U.S. law targeting forced labor and other alleged human rights abuses in the Xinjiang region of China has upended supply chains worldwide since it took effect in June 2022. In the first year and a half that this law has been in force, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) denied entry to 2,500 shipments worth a combined $2.2 billion. Moreover, the vast majority of the shipments came to the U.S. not from China but from other countries, and were blocked because components were traced back to Xinjiang.

This has implications for boards:

- As enforcement of the U.S. law is enhanced and other jurisdictions enact similar import controls, as part of their risk oversight role, boards should satisfy themselves that their companies have mechanisms and controls in place to provide reasonable assurance of compliance with these laws.

- Boards need to be aware that, if a company shows up in reports that note potential problems or violations, it will need a strategy to get ahead of the story to mitigate reputational risk and prepare for any government action.

- Such reports also can trigger shareholder demands to take action against management or board members, or may lead to books and records demands to find evidence of non-compliance with these laws.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) was prompted by concern within the U.S. Congress and the Biden administration that forced labor and other abuses against the Uyghur ethnic group are widespread in Xinjiang. Under the law, the CBP must presume that any goods mined, produced or manufactured in whole or in part in Xinjiang, or produced by entities blacklisted under the law, have been made with forced labor, and are prohibited from entering the U.S.

Despite the robust enforcement of the UFLPA and the resulting risk to importers, a number of myths and misconceptions persist:

Myth #1: The UFLPA only applies to imported goods whose country of origin is China. The UFLPA applies to goods that contain any inputs — no matter how small — that are made in Xinjiang or by an entity on the UFLPA “Entity List.” All such goods are presumed to be the product of forced labor. The country of origin of the good as a whole is irrelevant. As the pie chart shows, China is the country of origin for only 13% of shipments detained under the UFLPA. The vast majority of detained goods were made in Malaysia (54%), Vietnam (26%) or Thailand (7%).

Myth #2: Only cotton, tomatoes and solar panels face a meaningful risk of being detained. When Congress passed the UFLPA, it identified cotton, tomatoes and polysilicon (a key element used to make solar panels) as high-priority enforcement targets. Public discourse has heavily focused on forced labor risks associated with textiles and solar panels. But a much wider array of goods are currently at risk of detention. In a 2023 report, an interagency task force determined that a wide range of additional goods are at a high risk of being tainted by forced labor:

- Some agricultural products.

- Electronics.

- Lead-acid and lithium-ion batteries.

- Automobile components.

- Downstream products of vinyl, copper, aluminum and steel.

Indeed, more shipments of industrial materials and electronics have been detained than shipments of apparel and textiles. Recent additions to the UFLPA “Entity List” mirror this: Network technology, chemical and biotechnology companies were added in 2023.

Myth #3: NGO reports on Xinjiang don’t need to be taken seriously. When assessing supply chain risks, companies ignore at their peril the reports of journalists, academics and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The task force mentioned above and CBP pay close attention to NGO reporting on forced labor in Xinjiang. The task force has “extensive engagements” with NGOs to understand forced labor schemes in Xinjiang. Similarly, the State Department has cited numerous NGO reports on forced labor abuses. Beyond their influence with the government, NGO reports can harm a company’s reputation. For instance, an October 2023 NGO report mapped the Xinjiang mining industry and identified hundreds of large companies that may indirectly source gold from these entities.

Myth #4: ESG certifications adequately address forced labor risk. In assessing whether a supplier uses or benefits from forced labor, companies may be tempted to rely on third-party certifications that are based on environmental, social or governance (ESG) considerations other than forced labor. For instance, the London Base Metals Association’s Responsible Sourcing Programme and the Responsible Minerals Initiative provide certifications based largely on whether a company is operating in or sourcing from a conflict-affected, high-risk area. But given their focus on conflict minerals, these certifications are not reliable measures of potential forced labor risk. They are not a substitute for supply chain due diligence targeting forced labor.

Myth #5: CBP doesn’t have the resources to implement the UFLPA. CBP received increased funding in FY 2022 to enforce the UFLPA, and the administration has urged Congress to allocate additional resources. Going forward, CBP’s enforcement efforts will likely continue to widen in scope and become more sophisticated, reflecting new hires, new technology and enhanced training. This increases the likelihood that CBP will be able to accurately trace shipments of goods with a Xinjiang nexus further up the supply chain, and highlights the importance of having robust diligence measures in place to preemptively identify any such goods before they are detained at the border.

Myth #6: Small shipments won’t be scrutinized. Currently, shipments of goods valued below the de minimis threshold of $800 are exempt from import duties and do not go through the formal entry process at the border. CBP has historically applied less scrutiny to these “informal entries,” as it generally has less reportable information on them. This can make it difficult for CBP to assess the possible forced labor risk associated with such shipments, and detentions rarely occur. But there is growing interest on Capitol Hill in changing the de minimis regime and the administration has signaled that it may increase scrutiny of de minimis entries using its existing authority.

Myth #7: Companies need only focus on complying with U.S. law. Several other countries have adopted or are considering laws targeting the problem of forced labor. These laws broadly fall into two camps.

- Reporting requirements. Under the U.K.’s 2015 Modern Slavery Act, companies that meet certain financial thresholds must publicly disclose their efforts to eradicate forced labor from their supply chains. The government can “name and shame” companies that don’t produce the required statement, but it is not empowered to detain or investigate goods that may have been made with forced labor. Similarly, the 2021 German Supply Chain Act, Canada’s new Act on Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour, and the EU’s proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive all impose diligence and reporting obligations on certain companies.

- Import prohibitions. In 2020, Canada implemented an import ban on goods mined, manufactured or produced wholly or in part by forced labor. Likewise, the EU is currently considering a similar regulation that would prohibit the importation and sale of goods in the EU that are made with forced labor.

How Should Companies Respond?

CBP continues to ramp up its enforcement of the UFLPA, and an increasingly broad range of goods are now under scrutiny. To avoid the risk of goods being detained at the border, companies should implement robust policies and procedures to identify any supply chain links with Xinjiang. Companies should adopt a risk-based approach to forced labor diligence, taking into account the specific characteristics of the supply chains at issue. Among other steps, companies should consider the following:

Supply Chain Mapping

- Work with first-tier suppliers — especially high-volume suppliers or suppliers of high-risk items — to map their supply chains.

- Regularly screen these suppliers against the UFLPA Entity List.

- Review NGO reporting to identify any high-risk entities or goods.

Collect Key Documents

- For high-risk items, work with suppliers to collect documents for each stage of the supply chain, such as bills of lading, purchase orders, payment records, etc.

Establish Enforceable Standards

- Create a supplier code of conduct that prohibits the use of forced labor.

- Include contractual provisions that prohibit forced labor and ensure that this prohibition is heeded by upstream suppliers.

View other articles from this issue of The Informed Board

- Emerging Expectations: The Board’s Role in Oversight of Cybersecurity Risks

- AI Executive Order: The Ramifications for Business Become Clearer

- A Guide for Directors to Political Law Issues in This Election Year

- Shareholder Activism Continues To Increase and Spread in Europe

- Podcast: CEO Succession Planning on a Clear Day

See all the editions of The Informed Board

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.