See all chapters of Encyclopaedia of Prudential Solvency and A Guide to Solvency II.

Introduction

This chapter discusses prudential insurance regulation in Japan. Japan is the fourth-largest insurance market in the world, with a broad customer base and a varied range of offerings. This profile, coupled with ongoing regulatory evolution, has resulted in Japan becoming an increasingly attractive location for foreign participation in insurance and reinsurance activity.

Japan holds a 5% global market share, with insurance premium volumes of $363 billion in 2024, following only the US, China and the UK in its hold of the world’s insurance market. Traditionally dominated by life insurance, Japan’s insurance market has seen increasing competition in recent years, with the rise of foreign insurers and new market entrants into the reinsurance sector.

The life insurance market in Japan is relatively consolidated, with a total of only 41 domestic entities on the regulator’s list as of 6 June 2024, of which 12 are foreign-owned.1 Top players among these domestic life insurers have a significant role as investors in Japanese and global markets, with over $2 trillion in assets. These domestic insurers have been continually expanding overseas, making acquisitions in the US and London insurance markets as well as investing in Southeast Asia and the BRIC countries. Japan’s declining population, and the resulting need for domestic insurers to diversify their traditional businesses, has increased this acquisitive trend.

By comparison, on the regulator’s list of non-life insurance companies, a total of 33 domestic entities are listed as of 12 January 2022, of which 7 are foreign-owned, and 22 branch offices of foreign non-life insurance companies are listed as of 10 August 2023.2

The Japanese insurance market is attractive for foreign insurers for several reasons. It is one of the largest and most mature insurance markets globally, with a broad customer base and a culture of high levels of household savings, providing opportunities for growth and investment. Moreover, Japan’s aging population creates demand for a range of offerings, particularly in the life and longer-term health-care spaces, providing a venue for insurers to cater to evolving and unique customer needs.

1. The Legal Framework

Regulation of the Insurance Industry in Japan

Japan’s insurance and reinsurance industry is regulated primarily by the Insurance Business Act of 1995, with supplemental rules in the Enforcement Order of the Insurance Business Act (1995) and the Ordinance for the Enforcement of the Insurance Business Act (1996).3

The Financial Services Agency

The regulatory authority for the insurance industry in Japan is the Financial Services Agency (FSA), which is responsible for, among others:

- ensuring the stability of Japan’s financial system and the protection of depositors, insurance policyholders and securities investors;

- maintaining a well-functioning financial system through its planning and policy-making activities; and

- the inspection and supervision of private sector financial institutions and surveillance of securities transactions.

The FSA is empowered under statute to lead the planning and policy-making of financial systems and plays a general supervisory role in the writing of insurance contracts and the activities of insurance companies. Based on the Insurance Business Act, the FSA have the power to issue administrative dispositions to insurance companies, including orders for business improvement, orders for suspension of business and/or orders for cancellation of licenses.

In practice, broad discretion is given to the FSA. Insurers not only have to observe all laws and regulations, but must also follow the guidelines set by the FSA (referred to as the “Comprehensive Guidelines for the Supervision of Insurers”).

Equivalence

Japan was deemed Solvency II equivalent and was one of the first countries covered by the first wave of the Equivalence Assessment.

It was granted Temporary Equivalence for reinsurance, which expired on 31 December 2020.4 A joint statement by the FSA, the European Commission and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) was issued on 21 December 2020 to address the expiry of this temporary equivalence and the future implementation of Japan’s economic-value-based solvency regime.5

In addition, Japan has been granted provisional equivalence for group solvency until 1 January 2026.6 In practice, this means that UK and EU insurance groups can conduct their prudential reporting for a subsidiary in Japan under local rules instead of Solvency II, provided they are authorized to use deduction and aggregation as their method of consolidating group accounts.

The FSA established an Advisory Council on Economic Value Based Solvency. It is implementing an economic-value-based solvency regulatory framework over 2025-2026 that is closely aligned with Solvency II and the Insurance Capital Standard.7

‘Insurance Companies’: Operational Considerations

“Insurance companies” are strictly defined under the Insurance Business Act and, as is the case in many regimes, are generally not permitted to conduct any business other than underwriting insurance per the license and investing premium revenue and other assets, and any business incidental to the core insurance business.

Insurance companies are also restricted with respect to the ownership of subsidiaries in accordance with the Insurance Business Act. In the past, insurance companies were prohibited from, even through subsidiaries, engaging in non-insurance businesses. As a result of the deregulation, insurance companies may have subsidiaries engage in certain specified financial businesses such as securities and banking subject to the prior approval of, or prior notice to, the FSA. Additionally, insurance holding companies (i.e., companies for which the ratio of the total acquisition value of the shares of subsidiaries to the total assets exceeds 50% and whose subsidiaries are insurance companies) are subject to slightly more relaxed restrictions so that insurance holding companies may have subsidiaries engaging in other businesses with the prior approval of the FSA.8 Even though such approval or notification requirements are not technically triggered by acquiring equity interests in affiliated companies (meaning, generally speaking and subject to certain criteria and conditions, 20%-owned entities) by insurance companies or insurance holding companies, the Comprehensive Guidelines for the Supervision of Insurers basically impose effectively the same restrictions on the scope of businesses of such affiliated companies.

Relatedly, insurance companies generally are not allowed to obtain a stake in excess of 10% of the total voting rights of a domestic (non-insurance) company, except where permissible as holding ownership of subsidiaries and affiliated companies as described above.9

Life insurance and non-life insurance remains divided in Japan, with different types of licences required for each. Licences for life and non-life insurance business cannot be acquired by the same company, prohibiting them from running both businesses concurrently — composites are not permitted.10 However, because of the deregulation, life insurance companies are permitted to have non-life insurance subsidiaries and vice versa. Also, both life insurers and non-life insurers are free to offer insurance in the so-called “third sector” insurance market, for example medical care insurance, accident insurance or overseas travel insurance.11

Historical Context: Ongoing Regulatory Reforms

Japan is implementing ongoing regulatory reforms aimed at improving financial stability and competitiveness, and to align its regime with international standards. The current solvency regulations in Japan were introduced originally in 1996 and have in recent years been revised by the FSA to align more closely with global frameworks such as Solvency II and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors’ (IAIS’s) Insurance Capital Standard (ICS). This shift is intended to enhance the efficiency of the insurance market by introducing more sophisticated risk-based requirements, reflecting insurers’ actual risk profiles instead of relying solely on static capital buffers.

Japan began liberalising its insurance industry with the government’s “financial big bang” in the 1990s, where as part of an attempt to remedy economic stagnation in the early ’90s, the government introduced wide-ranging plans to re-regulate the financial services market modelled on similar frameworks globally. Insurance regulation saw a shift from its previous more rigid frameworks in favor of greater openness and flexibility. In 1998, for example, the relaxation of fixed insurance rates allowed insurers to compete more on price and service.

The introduction of the Insurance Business Act in 1995 exemplified the spirit of liberalisation and led to the increased presence of foreign life insurers, sparking a period of mass consolidation and restructuring of the non-life market. The Act saw industry regulators take a more principles-led approach, with a greater emphasis on the protection of policyholders. The revised Act also permitted non-life insurers to enter into the (previously cordoned off) life insurance market through subsidiary structures, promoting greater competition in the area. The Insurance Act of Japan (2008), which came into force in 2010, modernised insurance contract law in Japan, in both form and substance, after it had survived for nearly 100 years without substantial modification.

Between 1997 and 2000, foreign direct investment in Japan’s financial and insurance sectors was 11 times greater than what it had been between 1989 and 1996. Foreign insurers have since been able to increase their market share and now account for eight of the top 20 life insurers in Japan. In the non-life space, 22 of 55 listed general insurers in Japan are branch offices of foreign insurance companies, and seven of the remaining 33 domestic insurers are deemed “foreign-owned”, meaning they have an overseas-held stake of 50% or more.12

Deregulation and the end of tariffs in the late 1990s also ignited changes in reinsurance purchasing in Japan. Despite the size of the non-life market and exposure to natural disasters, a major feature of the Japanese reinsurance market since the postwar period had been for the bulk of reinsurance to be retained within the market through a variety of pooling arrangements and exchanges. For example, the government insured 60% of compulsory motor insurance in the late 1990s, with the remaining 40% ceded to the Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance Pool, a public-private partnership involving government contributions. It was only since the liberalisation of the ’90s and a sweep of natural disasters (such as Typhoon Mireille in 1991, with insured losses of $3.8 billion) that these pooling structures started disbanding and Japanese insurers began to arrange their own reinsurance facilities. These movements in reinsurance are only just beginning, with further regulatory reforms in progress.

2. Japan’s Prudential Regime

Capital Requirements for Insurance Companies in Japan13

Under the Insurance Business Act, among other financial regulations, insurance companies are required to satisfy the following requirements:

- Minimum capital requirement: The amount of stated capital (in the case of a stock corporation) or foundation funds (in the case of a mutual company) of each insurance company must be 1 billion yen or more.

- Policy reserves: Insurance companies are required to provide policy reserves so that they can fulfil their future obligations under the insurance policies they have underwritten.

- Policyholder dividends: The distribution of policyholder dividends by insurance companies must be made in a fair and equitable manner in accordance with the related regulations.

- Solvency Margin standard: As a regulatory measure of the ability of insurance companies to fulfil insurance and other claims upon the occurrence of unforeseeable events, including natural disasters, the Solvency Margin regulation was introduced for both life and non-life insurance companies on a nonconsolidated basis from the fiscal year ended March 1997 and has been improved since then. For the purposes of the Solvency Margin regulation, the nonconsolidated Solvency Margin ratio for insurance companies is calculated as the following:

Since 31 March 2012, the Insurance Business Act also introduced the consolidated Solvency Margin ratio regulation, covering insurance companies or insurance holding companies and their subsidiaries and affiliates.

From the fiscal year ending 31 March 2026, Japan will move to an Economic-Based Solvency Ratio (see section 6 below).

The Solvency Margin (the numerator of the nonconsolidated Solvency Margin ratio)

The Solvency Margin is calculated as a buffer in a company’s assets covering its liabilities — in other words, the difference between assets, A, and liabilities, L: S=A-L. The FSA lists the following as being included:

- Capital

- Revaluation differentials on securities are deducted to avoid double counting.

- Capital-like reserves

- Price fluctuation reserve

- A certain percentage of assets is set aside for price fluctuation risks.

- Contingency reserve

- A certain percentage of premium or net amount at risk is set aside for insurance risks and major catastrophe risks.

- General allowance for possible loan losses

- Price fluctuation reserve

- Unrealised gains/losses on securities and real estates

- Net unrealised gains/losses on available-for-sale securities (x 90% if gains; x 100% if losses)

- Deferred gains/losses on hedges (x 90% if gains; x 100% if losses)

- Net unrealised gains/losses on land (x 85% if gains; x 100% if losses)

- Subordinated debts that meet certain requirements, including deferral of interest payment obligations

- Deduction: Stocks and subordinated debts invested in insurance companies or any subsidiaries, etc.

- Margins for prudence contained in statutory provision

The Risk Amount (the denominator of the nonconsolidated Solvency Margin ratio)

The Risk Amount is the total amount of risks, which is calculated differently for life insurers and non-life insurers and represents risks which will exceed their usual estimates, such as the risk of catastrophic loss or a sharp value in the reduction of their assets. The following table describes major risk categories:

| Major risk category | Case assumed | Amount measured | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance risks (life insurance risk, non-life insurance risk and third-party insurance risk) | Insurance claims payment is higher than normal expectations. | Certain level of insurance claims payment minus normally expected level | |

| Assumed yield risks | Investment income earned is lower than originally assumed yield. | Expected amount of the gap | |

| Asset management risks |

|||

| Price fluctuation risks | Capital loss is higher than normal expectations. | Amount remaining after deducting the effects of diversified investment from the sum of the balance sheet amounts of risky assets multiplied by the risk factor, depending on the type of asset | |

| Credit risks | Counterparty defaults. | Expected amount of loss (including securitized assets) | |

| Other risks for subsidiaries or affiliate companies, derivative transaction, credit spread, reinsurance and reinsurance recoverable | |||

| Major catastrophe risks (general insurance only) | A natural disaster strikes. | Amount of damage caused by the largest earthquake or typhoon | |

| Business management risks | Something not in the above categories happens. | 2% or 3% of the total of the other risks | |

The Solvency Margin ratio as well as its components are disclosed to the public for every insurance company.

Early Remedial Actions and Early Warning System

In general, an insurance company will be considered in sound condition if the Solvency Margin ratio is 200% or more. If the Solvency Margin ratio falls below 200%, the FSA shall take early remedial action on the basis of the provisions of Article 132 of the Insurance Business Act. The objective of early remedial action is to ensure the sound and proper business operation of an insurance company and the protection of policyholders by enabling the FSA to urge insurance companies to maintain sound management with regard to their Solvency Margin ratios. Measures range from submitting and implementing business improvement plans to partial or total suspension of operation of the business of the insurer for a period.

In 2003, the FSA revised its administrative guidelines and introduced an early warning system. The FSA may request further reports and issue orders as necessary, even if the Solvency Margin ratio of a company is above the regulatory minimum, 200%, and therefore not technically subject to early remedial actions as described above. For instance, if the following are areas of concern, it may ask for these information items, among others:

- Profitability: Profit breakdowns and their projections.

- Credit risk management: Concentration of major credit exposures.

- Market risk management: Impact of price fluctuation of securities.

- Liquidity risk management: Asset portfolio and trend of policies.

3. Key Considerations for Foreign Insurers

Foreign Participants: Capital and Licensing Requirements

The above general restrictions also apply to foreign insurers. Foreign insurers are only allowed to conduct insurance business in Japan if they have opened either: a local Japanese subsidiary in the form of a Japanese stock company under the Company Act of Japan; or a “branch” in Japan (where instead of a capital requirement, the branch is required to deposit a minimum of 200 million yen, which is approximately $1.4 million, to the deposit office to protect policyholders).14

Once they have opened a subsidiary or branch in Japan, foreign insurers will have to obtain an applicable licence from the FSA. This allows the FSA to have administrative power over foreign insurers. The general rule is that unless they are licensed, foreign insurers are prohibited from concluding any insurance contracts that insure any person with an address, residence or property in Japan, or any vessel or aircraft registered in the country.15

Applying for a Licence

An FSA licence is not issued unless the FSA is convinced of the applicant’s credibility in terms of sufficient financial assets, human resources and business projections. During the licensing procedure, the FSA examines the company’s documents, including:

- General policy conditions;

- The business method statement;

- The premium and reserve calculation method statement;

- Business projections (generally for 10 years);

- Directors’ résumés; and

- Information on major shareholders of the applicant.16

The FSA endeavours to make a decision whether to grant a license within 120 days after receipt of the licensing application — this is called the “standard processing period”.17 However, this rule only applies on a best-endeavours basis, and is interpreted to commence when the formal application documents are filed. In practice, the foreign insurer or its subsidiary will hold many discussions with the FSA about the application documents before the formal filing, and this discussion period will likely take at least a year.

Strict penalties apply — engaging in insurance business without the necessary licence is subject to punishment by a maximum three years’ imprisonment or a maximum 3 million yen fine.18

Specific Exceptions to the Licensing Requirement

Foreign insurers may enter into certain insurance contracts without obtaining the applicable licence. These comprise:

- Reinsurance contracts;

- Marine insurance contracts that cover vessels registered in Japan, cargo transported by such vessels or liabilities that arise therefrom;

- Aviation insurance contracts that cover aircraft registered in Japan, cargo transported by such aircraft or liabilities that arise therefrom;

- Space insurance contracts that cover launches into outer space, cargo transported by such launches or liabilities that arise therefrom;

- Insurance contracts that cover cargo originating in Japan and in the process of being shipped overseas; and

- Overseas travel insurance contracts that cover injury, illness or death, or cargo of overseas travelers.19

Moreover, the licensing restriction does not apply to any insurance contract where the FSA have granted advance ad hoc permission to an applicant wishing to purchase insurance from an unlicensed foreign insurance company.20

4. (Re)insurance Transactions

(Re)insurance Activity

With domestic regulation allowing for foreign insurers to become licensed to operate in Japan, transactions structured through offshore reinsurance have picked up in recent years.

Japan’s primary insurance and reinsurance sectors have also experienced dynamic growth. The Japanese market is mature and highly competitive — both of which are critical elements necessary for the growth of reinsurance.

As with the US, recent primary insurance market growth in Japan has been driven by sales of savings-oriented products for mortality and annuity segments. These movements have been driven by an aging population. Also, limitations on public health-care benefits mean that products offering morbidity coverage are in high demand. The capital- and asset-intensive nature of these products is driving the need for new partnerships to assist primary writers with sophisticated underwriting for complex products; balance sheet relief for their capital intensity; and related asset management partnerships. Reinsurance is an effective tool to address all three of these objectives.

The last 18 months have yielded a high volume of announced transactions, indicating the start of a reinsurance boom. These transactions are structured on both an in-force or “block” basis — with blocks of existing business — and a “flow” basis — with quota share reinsurance of future premiums, with a preference for flow. These differing structures are designed to achieve various objectives for the Japanese cedants.

Transaction Characteristics

Most of these transactions are characterised by a cession from an “onshore” Japanese life and annuity insurer to an “offshore” reinsurer (generally, a Bermuda Class E long-term insurer). The fact that most of these transactions involve a cession to Bermuda signals the FSA’s comfort with the Bermuda Monetary Authority as a regulator — Bermuda has received equivalence under EU and UK Solvency II and with the NAIC as a qualified jurisdiction (although see further below).

As a general trend, partnerships are between the largest players in the Japanese life/annuity market and, usually, large reinsurers. Several in-force transactions with ceded reserves in the multibillions may also signal a desire for capital relief.

Most significant transactions have also been placed with reinsurers affiliated with large asset managers, signaling that Japanese insurers are looking for support with investment management. Many of these transactions have been on a flow basis, potentially indicating a desire for support with respect to asset origination at the time of contract inception and greater ease in obtaining the necessary capital treatment.

(No) Fronting Restrictions as Such

Fronting is not expressly prohibited or permitted in Japan, and there are no explicit expectations with regard to the cedant’s retention.

5. (Re)insurance Transactions – Practical Considerations

Exemption From the Licensing Requirement

Reinsurance transactions by foreign companies are exempt from the licensing requirement (outlined above) under the Japanese prudential solvency regime, although it is nonetheless important that they receive the correct capital treatment on the insurer’s balance sheet in order to be effective as an eligible risk mitigation technique.21

As to licensing, by analogy, the appropriate test looks similar to the “characteristic performance” test familiar in the UK and Europe in order to determine the regulatory perimeter. Under the Japanese regime, if a reinsurer operates business on an “offshore” basis (i.e., conducting all underwriting, claims handling, contract negotiations and other activities from outside Japan and not utilising its own employees or agents to conduct any such activities in Japan), then it is not required to be licensed and therefore will not be subject to FSA supervision, any regulatory (including reporting) obligations or (for the reinsurer) any capital requirements, regardless of the amount of business it conducts with Japanese cedants.

Japanese cedants, in turn, are subject to regulatory requirements to obtain credit for reinsurance on their financial statements, and may request information from foreign reinsurers in order to comply with their regulatory obligations.

Reinsurance Policy Reserves

Reinsurance transactions between Japanese insurers, as well as those with overseas insurers that are licensed in Japan, are classed as generally exempt from the general requirement on licensed insurers to hold reserves for the policies they have insured. Japanese cedants get credit for reinsurance in respect of policy reserving, however there must be a high possibility of recovery under the reinsurance contract. They must also do due diligence to understand the reinsurance counterparty in as much detail as much as possible to evaluate the possibility of recovery.

This exemption may also be invoked by Japanese cedants in respect of foreign reinsurers, but only to the extent that the reinsurance would not impair the financial soundness of the cedant, considering the foreign reinsurer’s business and financial condition. There is no specific test based on specific monetary thresholds or limits regarding this exemption. However, the FSA Guidelines22 suggest that this exemption may be invoked in respect of foreign reinsurers, for example where:

- the maximum reinsurance payment per single insured event is less than 1% of the cedant’s total assets, or

- the cedant has not yet accumulated liability reserves corresponding to the business for which reinsurance is effected.

In each case there must be no concern that the foreign reinsurer would fail to make the reinsurance payments due to insolvency or other reasons.

In practice, this means that Japanese cedants may ask a foreign reinsurer for information, materials and other evidence regarding their business and financial condition in order to fall under this exemption to hold policy reserves.

It is expected that the new economic-value-based solvency regulations (see section 5 below) will come into effect from this financial year (ending 31 March 2026). The finalised rules are expected to be announced in the summer of 2025. We note that the FSA have run extensive field trials for the new standards, some of which give may give an insight into the possible future treatment of reinsurance.23

In these field studies reinsurance exposure / counterparty risk is introduced, in a similar manner to the IAIS’s ICS. AM Best ratings are suggested to be used to rate exposures. If the required capital insurers must hold is reduced by reinsurance, the required capital for the credit risk (i.e., the counterparty risk) must be calculated for that reduction of the required capital. This is calculated by multiplying the decrease in required capital from reinsurance by the risk factor split by rating class of reinsurer and maturity. Where credit risk reduction techniques such of use of collateral and guarantees are used, there is guidance on how that should be treated in the context of reinsurance.

In late January 2025, it was reported that the FSA had started to survey Japanese life insurers to examine the potential risks tied to their rapidly growing practice of transferring policy liabilities to reinsurers often backed by global private equity firms. According to a March 2025 report, the FSA is asking Japanese life insurers about the scale of their reinsurance practices and the types of contracts they have in place, and is also interested in the concentration of risks with reinsurers operating in Bermuda.24 Note that despite this attention there have been no official announcements or regulatory actions by the FSA so far, only reports that this information-gathering exercise is taking place. This may suggest, however, that the FSA would consider introducing new regulations or restrictions on reinsurance transactions in the near future.

6. Economic-Value-Based Solvency Regulations

Japan is introducing new economic-value-based solvency regulations in 2025-2026. The FSA is aligning with the ICS issued in final form by the IAIS in December 2024.25 Shigeru Ariizumi, vice minister for international affairs at the FSA, is the current IAIS Executive Committee chair, undertaking a two-year term that will run through to November 202526 .

Due to the introduction of these new regulations, many Japanese insurance companies (especially life insurance companies) are considering entering into new reinsurance agreements with reinsurers. Both flow and block reinsurance are being used, often in the form of asset-intensive reinsurance or “funded reinsurance”, which is gaining momentum in the Japanese life insurance market. This is because solvency requirements in Japan can be profoundly affected by fluctuations in interest rates, especially when an insurer has existing blocks of insurance contracts with high long-term interest rates — meaning reinsurance agreements are seen as a way to hedge against this risk. This has resulted in a surge of reinsurance deals in the Japanese market, creating opportunity for overseas participation.

The FSA is implementing the new economic solvency regulations (ESR) from the fiscal year ending 31 March 2026, with the first required reporting of the new standard taking effect taking place from that date. Insurance companies in Japan will have to submit business reports pursuant to the new legislation from then onwards. The current Solvency Margin Requirement will no longer apply after this time.

Alignment With ICS

Japan’s new regulations are designed to be generally aligned with ICS, but with slight adjustments. For example, the coefficient for calculating life and non-life insurance risks will be calibrated to reflect the characteristics of Japanese insurance companies — many of Japan’s insurers are small or medium-sized, whereas the coefficient in the calculation of ICS is based on data mainly collected from large international insurance groups.

Background to the ESR

The FSA have noted27 the significance of introducing new regulations can be summarised from the following three main perspectives:

- Protection of policyholders: By introducing regulations that can reflect the medium- to long-term soundness of insurance companies in a forward-looking manner, insurance companies will be required to ensure the ability to fulfil insurance obligations even when risks emerge, thereby protecting policyholders.

- Improving insurance companies’ risk management: For companies that have already adopted an economic-value-based approach, it is expected that the consistency between internal control indicators and regulatory indicators will be improved, and for companies that have not yet adopted an economic-value-based approach, the introduction of risk management based on economic value will be promoted.

- Provision of information to consumers, market participants, etc.: By disclosing information based on uniform standards based on economic value, it is expected that the provision of information on financial soundness will be enhanced with a certain degree of comparability, and that the governance and discipline of insurance company management will be improved through dialogue between insurance companies and external stakeholders.

Three Pillars

The ESR has a three-pillar approach:

Pillar 1 (solvency regulation): Establishes common standards for solvency ratios and provides a framework for supervisory intervention as a backstop to protect policyholders (the basic structure is the same as ICS). It involves:

- evaluating an insurance company’s assets and liabilities on an economic-value basis;

- measuring the amount of risk (required capital) that will arise under a stressed environment, and

- assessing the sufficiency of capital (eligible capital) against that.

Pillar 2 (internal controls and supervisory verification): Captures risks that cannot be captured by the first pillar, verifies the internal controls of insurance companies, and promotes their sophistication.

Pillar 3 (information disclosure): Promotes appropriate dialogue between insurance companies and external stakeholders, and ultimately exerts appropriate discipline on insurance companies.

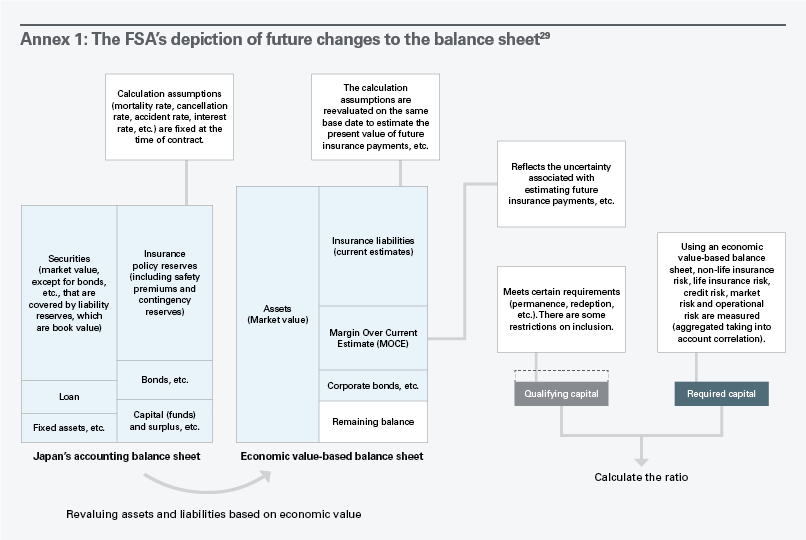

The FSA have produced a useful summary of the differences between Japan’s current accounting balance sheet and its economic-value-based balanced sheet, which is reproduced in Annex 1 to this chapter.

Changes are also proposed to the Early Remedial Actions system, changing the solvency ratio percentages to align with the new ESR.

Field Test Results

As part of its review of economic-value-based evaluation and supervision methods, the FSA conducted several ESR calculations based on the Market Adjusted Valuation (MAV) methodology adopted during the ICS monitoring period.

The tests showed the average ESR for life companies as of 31 March 2023 was 220% and for non-life companies 182%. Overall the largest risk was equity risk.28

7. Interaction With the UK Regulatory Regime

Historically Japanese insurers have sought to use the UK “Part VII” process, which is ultimately effected by the UK courts, to transfer their insurance liabilities to another insurer in circumstances where Part VII can apply. In some cases, this includes circumstances where both the transferor and transferee insurers are Japanese insurers. While a statutory transfer mechanism for books of insurance does exist in Japan, this requires the authorisation of the prime minister, a special resolution of the shareholders of both transferor and transferee, and the notified consent of all affected policyholders. However, several Japanese insurers have historically opted to use the Part VII process to dispose of legacy businesses and action portfolio transfers.

Moreover, in the absence of an equivalent framework being available under Japanese law, several leading Japanese trading companies have historically set up insurance broking subsidiaries in the UK in order for them become involved in the insurance arrangements of their parent.

Japanese insurance companies have also undertaken sustained outbound deal activity as they pursue business outside their home market. The main driver for this M&A is promoting diversification where a shrinking population has weighed on domestic growth. At the same time, foreign insurance companies and insurance brokers are increasingly making inroads into the Japanese markets.

8. Conclusion

It is evident that the regulatory framework in Japan is designed to balance the protection of policyholders and regulatory equivalence, with the need for insurers (and Japan) to remain competitive.

Not only are Japanese insurance companies vibrant participants in the global market, overseas insurers and reinsurers are increasingly being seen to make the most of the insurance opportunities opening up in Japan. The strength of the Japanese insurance industry and the FSA’s encouragement of innovation should lead to further regulatory evolution as new challenges arise.

With special thanks to Skadden Tokyo for their assistance with research for this publication.

_______________

1 List of licensed (regulated) Financial Institutions, Financial Services Agency.

2 Ibid.

3 See the Insurance Business Act (Act No, 105 of 1995), the Enforcement Order of the Insurance Business Act (Cabinet Order No. 425 of 1995) and the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Insurance Business Act (Ordinance of the Ministry of Finance No. 5 of 1996).

4 Article 172(4), EC Delegated Decision (November 2015).

5 Joint Statement on Japan’s Temporary Equivalence Regarding Reinsurance and Enhanced Cooperation, European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (December 2020).

6 EC Delegated Decision, (November 2015).

7 The Advisory Council on the Economic Value-Based Solvency Framework, Financial Services Agency.

8 Article 271-22, Insurance Business Act (June 1995).

9 Article 107, Paragraph 1, ibid. Also, the Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade of Japan (1947) generally prohibits insurance companies from acquiring or holding voting rights of a domestic company in excess of 10% of its total voting rights without the prior approval of the Fair Trade Commission of Japan.

10 Article 3, Paragraph 3, ibid.

11 Article 3, Paragraphs 4 and 5, ibid.

12 List of licensed (regulated) Financial Institutions, Financial Services Agency.

13 https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/refer/ins/capital.html

14 Article 190, Paragraph 1 of the Insurance Business Act, and Article 24 of the Enforcement Order of the Insurance Business Act.

15 Article 185, Insurance Business Act (June 1995).

16 Article 187, ibid.

17 Article 246, Paragraph 1 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Insurance Business Act of 1996.

18 Article 315, Item 1, Insurance Business Act (June 1995).

19 Article 186, Paragraph 1, ibid.

20 Article 186, Paragraph 2, ibid.

21 Article 19, Item 1, Enforcement Order of the Insurance Business Act (December 1995).

22 See page 59 of the English translation linked here: https://www.fsa.go.jp/common/law/guide/en_ins.pdf.

23 https://www.fsa.go.jp/policy/economic_value-based_solvency/06_1.pdf, paragraphs 470-472, 485 and 501

24 Japan’s FSA Is Said to Examine Life Insurers’ Reinsurance Risks” (2 March 2024), Bloomberg.

25 Economic Value Based Solvency Regulations Updates, Financial Services Agency.

26 https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/news/2023/20231020/20231020.html

27 https://www.fsa.go.jp/policy/economic_value-based_solvency/07_2.pdf.

28 https://www.fsa.go.jp/policy/economic_value-based_solvency/06_3.pdf

29https://www.fsa.go.jp/policy/economic_value-based_solvency/07_2.pdf

This memorandum is provided by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.